One of the most important liturgical books in early medieval England was the Psalter. Some thirty Anglo-Saxon manuscripts containing the complete Psalter have survived, including no fewer than fifteen with (partial or complete) Old English interlinear glosses (that is: a word-for-word English translation between the Latin lines). While multiple manuscripts of the same well-known text may seem like a rather dull topic, the Old English glossed Psalters are fascinatingly different, as this blog post will demonstrate.

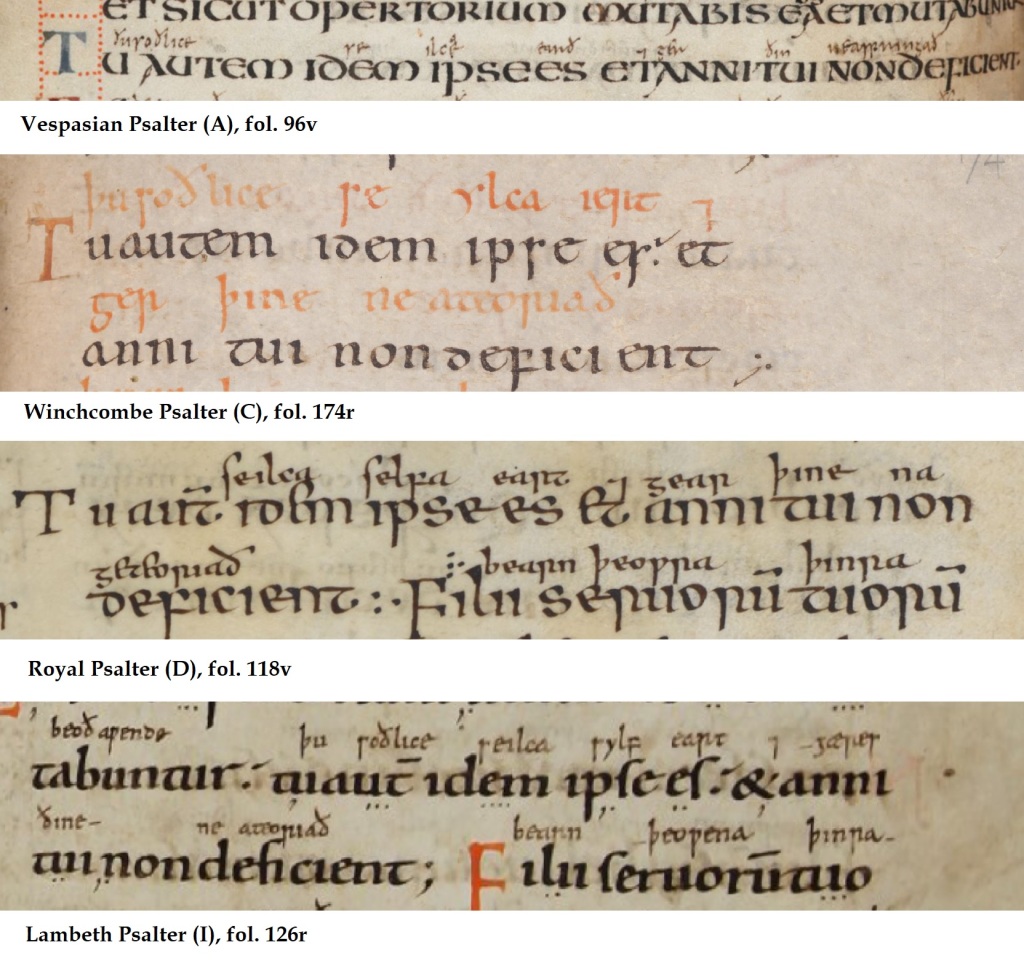

Different versions of the same Psalm verse (101:28)

To illustrate some of the diversity among the Old English glossed Psalters, here is the same Psalm verse (101:28 “Tu autem ipse es et anni tui non deficient”; You are truly the same and your years will not fail) in four different manuscripts with Old English glosses.

One clear difference between these Old English glossed Psalters is the scripts that the scribes used. The eighth-century Vespasian Psalter, for instance, uses an uncial script for the Latin text and is accompanied by a later, ninth-century Old English gloss in a much smaller minuscule script. In the Winchcombe Psalter (1025-1050), the same scribe was responsible for both the Latin and the Old English text, using a round insular minuscule for the Old English and a Caroline minuscule for the Latin, as well as alternating coloured inks (red for Old English; black for Latin). A similar combination of Caroline and insular scripts, though without the alternating colours, was used by the scribe of the mid-tenth-century Royal Psalter. The early-eleventh-century scribe of the Lambeth Psalter added a third layer of glosses, the dots underneath.

There are more differences if we turn to what the letters actually spell out. They each give the same Latin text (“tu autem idem ipse es et anni tui non deficient”), although there are some differences in abbreviations (e.g., the Vespasian Psalter and Winchcombe Psalter spell out “autem” in full; but the Royal Psalter and the Lambeth Psalter give “aut” with an abreviation mark; the latter also provides the ampersand “&” while the others give “et”). The Old English translations show more profound differences:

Vespasian Psalter: ðu soðlice se ilca earð 7 ger ðin ne aspringað

Winchcombe Psalter: þu soðlice se ylca iert 7 ger þine ne ateoriað

Royal Psalter: se ilca selfa eart 7 gear þine na geteoriað

Lambeth Psalter: þu soðlice se ilca sylf eart 7 gæres ðine ne ateoriað

These four Old English translations of the same Latin line clearly differ in spelling (ger, gear, gæres) and word choice (aspringað, ateoriað, geteoriað) – these differences are linguistically significant as we will explore further below.

Old English language through time and place

One variation factor among the Old English glossed Psalters is that they were written at different times and places, which means we can see diachronic and dialectal differences between them. A clear example is found in the Old English glosses for Latin “anni” [years] in Ps. 101:28 above: the Vespasian and Winchcombe Psalters give the form “ger”, the Royal Psalter gives “gear”, while the Lambeth Psalter gives “gæres”. The difference between the Vespasian and Winchcombe Psalter on the one hand and the Royal Psalter on the other is one of dialect: the Royal Psalter’s “gear” shows ‘palatal diphthongization’ (a singular vowel sound changes into a combination of two vowels, when preceded by a /j/-sound), which is a feature of the West Saxon dialect of Old English, while the Vespasian and Winchcombe Psalters give the Mercian dialect form without diphthongization: “ger”.

The Lambeth Psalter’s form “gæres” is actually grammatically incorrect and this form reveals that this gloss is later than the other ones. The -es ending here indicates that the word is plural, but this plural form is ‘not according to Old English grammar rules’. Here is a complex explanation: in ‘proper Old English’, the word “gear/ger” is a strong neuter noun with a long stem, which does not get an ending to mark the plural (just like modern English sheep: one sheep, two sheep; NOT two sheep-s). By the end of the Old English period, when the Lambeth Psalter was made, the grammatical system of Old English was starting to change and eventually the -s plural (originally reserved for strong masculine nouns) came to be used for all nouns with few exceptions (e.g., Modern English sheep~sheep, ox~oxen), because of a process called ‘analogy’ (frequently used forms become the norm). Long story short, the Lambeth Psalter’s “gæres” is a late form anticipating Modern English year-s, while the “ger/gear” form represents earlier Old English (this also explains why the Lambeth Psalter gives the vowel “æ”, which is a later development from West Saxon “ea”).

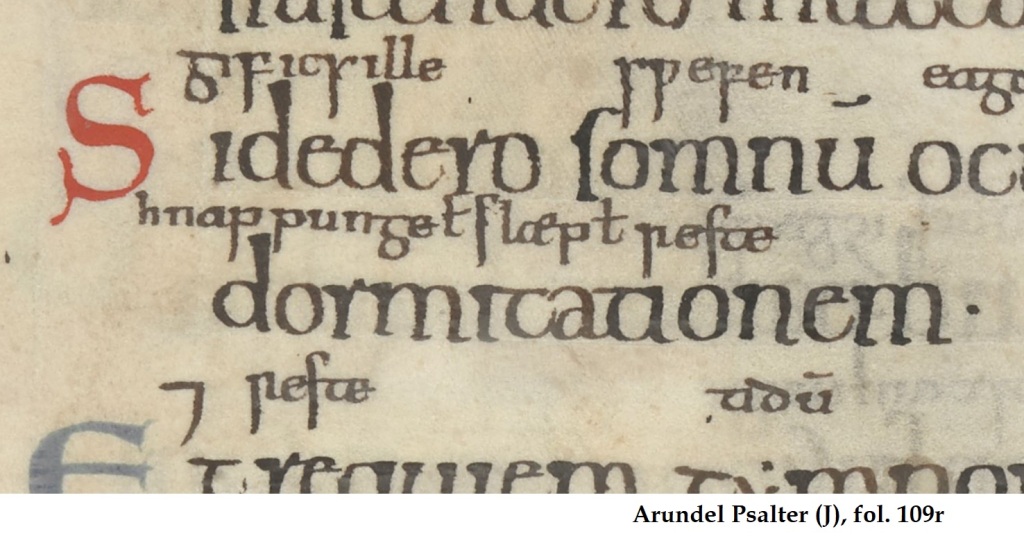

Other linguistic differences stem from word choice, which may be influenced by dialect or time of composition, but could also be due to the glossator’s personal preference. In Ps. 101:28, for instance, the glossator of the Vespasian Psalter decided to translate Latin “deficient” with a form of apsringan ‘to fall, cease, fall away’, while the other Psalters have a form of ateorian/geteorian ‘to fail, come to an end’. Either synonym works fine as a translation of the Latin. There are also cases where glossators gave multiple synonyms for one Latin word, such as the following example from the Arundel Psalter, which may come in handy if all this linguistic stuff has made you a little drowsy:

Rather than giving just one translation for the Latin word “dormitationem”, the glossator provides three alternatives: “hnappunge”, “slæp” and “reste” – nap, sleep or rest. This glossator certainly was not asleep on the job!

To gloss or not to gloss: Glossing techniques

Another fundamental difference between the Old English glossed Psalters lies in their differing glossing techniques. For instance, there are Psalters in which every individual Latin word is glossed, as in the Vespasian Psalter, Winchcombe Psalter and Lambeth Psalter, while other Psalters tend not to gloss personal and place names or common words. In the gloss for Ps. 101:28 in the Royal Psalter, the words “tu” and “autem” are not glossed as the glossator apparently assumed the reader would have been familiar with these basic words.

Another issue that is dealt with in different ways in various Old English glossed Psalters is the Latin syntax. The typical word order of Latin differs from that of Old English – for example, in Latin, the possesive pronouns often follow the nouns they modify, whereas in Old English they would typically precede the nouns: Latin “anni tui” (lit. ‘years your’) would be “þine gear” in Old English, ‘your years’. In most Old English glossed Psalters, the Old English glosses follow the Latin word order and, therefore, result in unnatural Old English phrases, such as “gear þine” in the Royal Psalter. However, the scribe of the Lambeth Psalter found a solution to this problem: he added so-called ‘dot glosses’ underneath the Latin words that indicated the Old English word order (I explain this system here: Reading between the lines in early medieval England: Old English interlinear glosses).

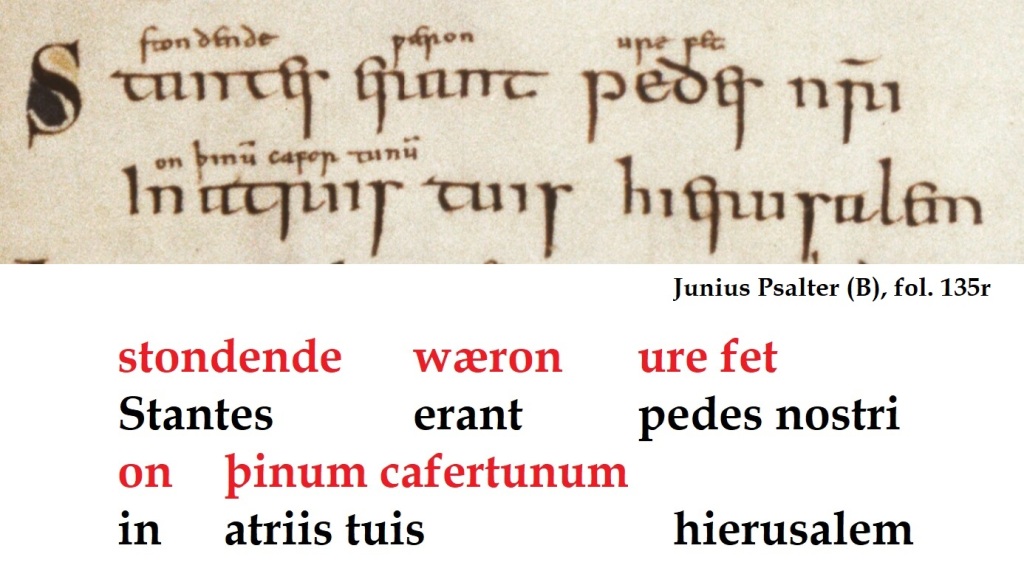

Other Old English glossators simply rearranged the word order of the glosses, like the one responsible for this Old English gloss of Ps. 121:2 (‘Our feet were standing in your courtyards, Jerusalem’) in the Junius Psalter:

Here the Old English glosses for the Latin phrases ‘pedes nostri’ and ‘atriis tuis’ have been ‘normalised’ to ‘ure fet’ and ‘þinum cafertunum’. You can also see that this glossator did not think it was useful to gloss the name Jerusalem.

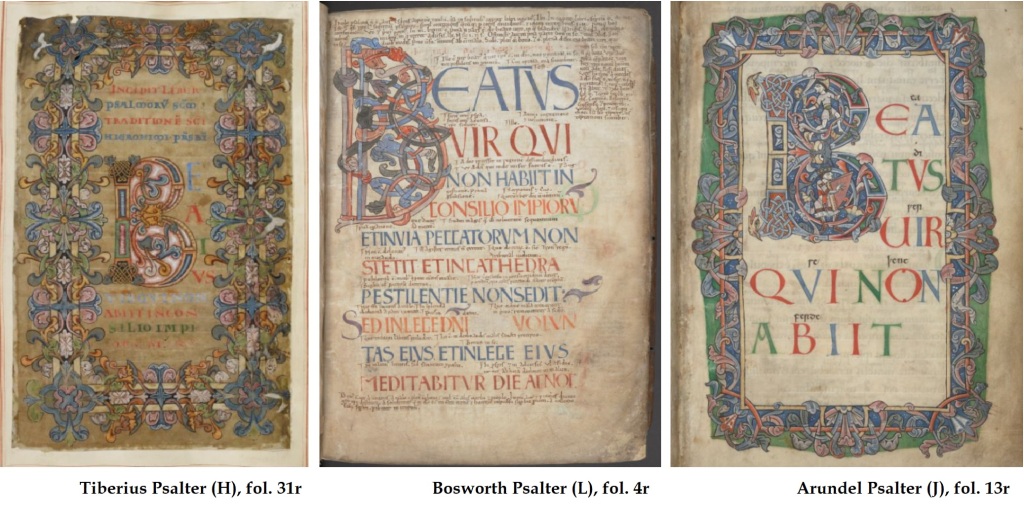

Beatus-ful illuminations!

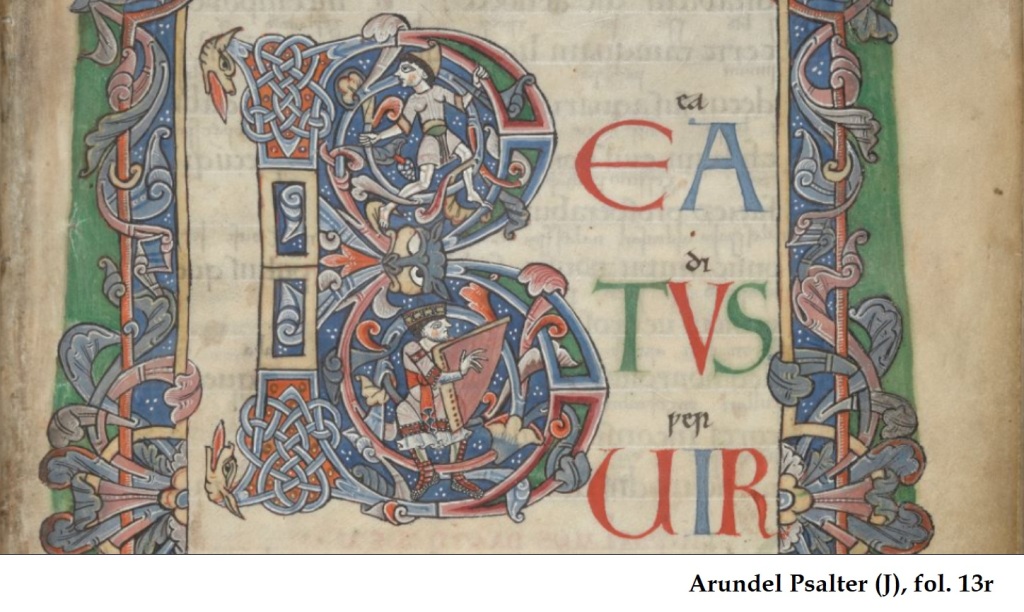

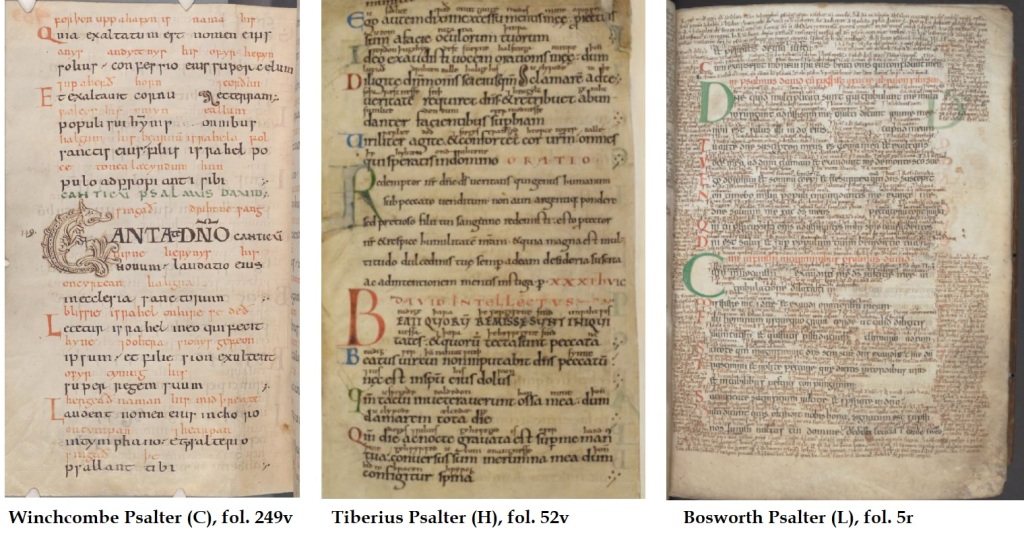

But it is not just linguistics that makes the Old English glossed Psalter fascinating things to look at: some of them are beautifully decorated! The opening lines of Psalms 1, 51 and 101, in particular, got additional artistic attention as they marked the beginning of three sections of fifty Psalms. Have a look at the opening of Psalm 1, which starts with ‘Beatus uir’ [‘Blessed man’], in three of the Old English glossed Psalters, below:

These so-called ‘Beatus pages’ give the Psalters a stunning opening and the page often comes with the creative use of different coloured inks. Note how the Bosworth Psalter alternates between blue and red lines, while the Arundel Psalter has letters in red, blue and green. The decorated border of the Tiberius Psalter is so thick that there is little room for text in the middle; the Arundel Psalter, meanwhile, has a thinner border but a bigger capital B; a so-called ‘historiated initial’, depicting King David (who was assumed the be the author of many Psalms):

While King David plays the harp in the historiated initial of the Arundel Psalter, to the right of the initial we find the Latin words ‘Beatus uir’, accompanied by the Old English gloss ‘eadi wer’ [blessed man].

Mis-en-page to avoid mess-on-page

Arranging a manuscript page for lines of Latin text that left enough room for the accompanying layer of Old English glosses required careful planning. Here are two examples of planned-out ‘mis-en-page’ (the way text appears on the page), as well as one example of a page on which there was not enough space for the huge amount of glossing (in this case explanatory glosses that were added later) :

The third example clearly has a more messy appearance, since the planned space for glossing was smaller than it needed to be.

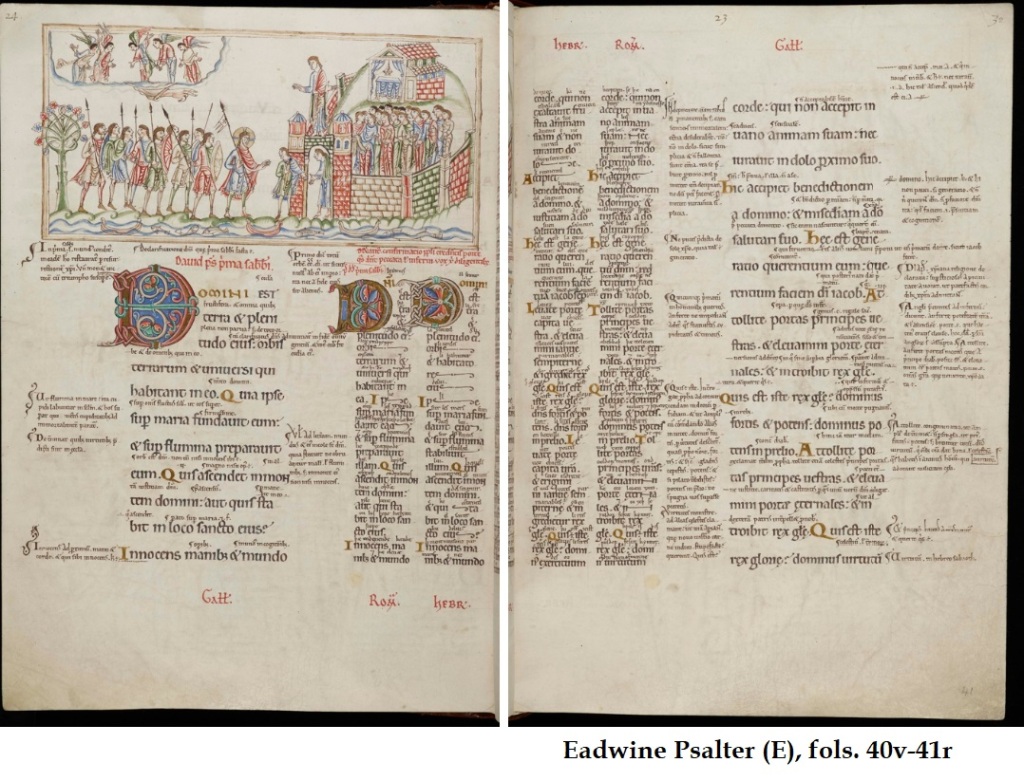

While correctly planning out a singular Latin text and one layer of Old English gloss was no mean feat, Eadwine, a twelfth-century monk from Canterbury, took on an even bigger challenge: the so-callled ‘Eadwine Psalter’ for which he was responsible is home to three different Latin versions of the Psalter, each accompanied with a different gloss, -and- a series of Psalter illustrations:

The broadly spaced Latin text on the outer edges of the left- and right-hand page is the Gallican version of the Psalter (marked “Gall.” on the bottom of the left page and on the top of the right page), with explanatory glosses in Latin between the lines and in bother margins. The second more narrow narrow column (marked “Rom.”) is the Romanum version of the Latin Psalter, with Old English interlinear glosses, while the column closest to the middle of the book (rightmost on the left page; leftmost on the right page) gives the Hebraicum version of the Latin Psalter, with Anglo-Norman interlinear glosses. Psalter-ception! Making sure that each page gave corresponding passages in the three Latin versions of the Psalter as well as making enough room for the glossing required Eadwine to carefully adjust the sizes of scripts, spacing and distribution of the text on the page. Managing all this, Eadwine certainly deserves the epithet of ‘s[c]riptorum princeps’ [master of scribes] with which he was described in the text surrounding his famous ‘author-portrait’ at the end of the Psalter that bears his name.

The language, glossing technique, illuminations and mis-en-page are but some of the fascinating aspects of the Old English glossed Psalters (others include annotations by later users, scribes making mistakes, curious initials and so on); in future blog updates, I hope to devote posts to individual Old English Psalters to create a fifteen-part series, starting with the Vespasian Psalter (A). Stay tuned!

If you want to be alerted to subsequent blog posts, make sure to subscribe to this blog, using the box below. If you can’t wait for a next blog post to appear, check out the following related blog posts:

- The Illustrated Psalms of Alfred the Great: The Old English Paris Psalter

- Reading between the lines in early medieval England: Old English interlinear glosses

- Triangular texts in three manuscripts from early medieval England

- Word processing in early medieval England: Browsing British Library, Royal MS 8 C III

List of Old English glossed Psalters

- Vespasian Psalter (A): London, British Library, Cotton Vespasian A.i

- Junius Psalter (B): Oxford, Bodleian Library, Junius 27

- Winchcombe/Cambridge Psalter (C): Cambridge, University Library, Ff.1.23

- Regius/Royal Psalter (D): London, British Library, Royal 2.B.v

- Eadwine Psalter (E): Cambridge, Trinity College, R.17.1

- Stowe Psalter (F): London, British Library, Stowe 2

- Vitellius Psalter (G): London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius E.xviii

- Tiberius Psalter (H): London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius C.vi

- Lambeth Psalter (I): London, Lambeth Palace, MS 427

- Arundel Psalter (J): London, British Library, Arundel 60

- Salisbury Psalter (K): Salisbury, Cathedral Library, MS 150

- Bosworth Psalter (L): London, British Library, Additional 37517

- Blickling Psalter (M): New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 776

- Fragments of Old English glossed Psalter (N): Cambridge, Pembroke College, 312, C, 1-2; Haarlem, Noord-Hollands Archief, 188 F 53; Sondershausen, Schlossmuseum, Lat. liturg. IX 1

- Paris, Biblitohèque Nationale, Lat. 8846 (O)

- Paris Psalter (P): Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Lat. 8824 (not a glossed Psalter; but a Psalter with facing Old English translation, see this blog post)

Relevant literature on the Old English glossed Psalters

- Philip Pulsiano, ‘Psalters’, in The Liturgical Books of Anglo-Saxon England, ed. R. W. Pfaff (Kalamazoo, 1995), 61-86.

Thank you so much …. what a wonderful report. I only have to see your name at the top and know I am in for a good read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So interesting – thank you very much, tim

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely excursion through the glossed Psalters. I am glad you ended with the Eadwine, one of my favorite and one that I spent some time with in person. It is a total immersive reading experience.

LikeLiked by 1 person