The Psalter was perhaps the best-known text among the Anglo-Saxons. As a result, many Psalters have survived from early medieval England. This blog post focuses on the Paris Psalter, which has been associated with Alfred the Great and features some beautiful illustrations.

The prose Psalm translations of Alfred the Great in the Paris Psalter

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, lat. 8824 (the ‘Paris Psalter’) is a unique manuscript dating to around 1050. The main texts of the manuscript are the 150 Latin Psalms with facing Old English translations: the first fifty Psalms are translated into Old English prose and another translator rendered the last hundred Psalms in Old English verse. Although the Paris Psalter does not mention the author of the Old English Psalm translations, the translator of the first fifty Psalms has been identified as none other than Alfred the Great (d. 899). The arguments for the attribution to Alfred concern the language of the prose translations (a ninth-century West Saxon dialect) as well as a twelfth-century chronicler recording that Alfred was working on a translation of the Book of Psalms but had not been able to finish it before he died. I have outlined these arguments in an earlier blog post on the Old English word earsling (the ancestor word of the popular insult ‘arseling’), which occurs only in the Paris Psalter (see: Arseling: A Word Coined by Alfred the Great? ).

Like the other translations associated with Alfred’s ‘educational revival’ (such as the Old English Boethius), the prose translations of the first fifty Psalms in the Paris Psalter are not entirely literal and often feature additional interpretations. A clear case in point is the rendition of Psalm 44:2 (My heart hath uttered a good word: I speak my works to the king: My tongue is the pen of a scrivener that writeth swiftly), which was expanded to:

As this passage illustrates, Alfred added allegorical interpretations of some of the phrases in the Psalm. These additions resulted in the Old English text being a lot longer than the Latin original. As we shall see, this difference in length caused some problems for the scribe of the Paris Psalter.

Scribe of the Paris Psalter: Wulfwine ‘the Lumpy’

The scribe of the Paris Psalter identifies himself in a colophon at the end of the manuscript:

Hoc psalterii carmen inclyti regis dauid. Sacer d[e]i Wulfwinus (i[d est] cognom[en]to Cada) manu sua conscripsit. Quicumq[ue] legerit scriptu[m]. Anime sue expetiat uotum.

[This song of the psaltery by the famous King David the priest of God Wulfwine (who is nicknamed Cada) wrote with his own hand. Whoever reads what is written, seek out a prayer for his soul.]

Wulfwine’s nickname ‘Cada’ means something like ‘stout, lumpy person’ (he is, by no means, the only Anglo-Saxon with a silly nickname, see: Anglo-Saxon bynames: Old English nicknames from the Domesday Book).

Richard Emms (1999) has suggested that Wulfwine ‘the Lumpy’ may have come from Canterbury. He noted, for instance, that the Paris Psalter shares two rare features with another manuscript from Canterbury: its awkwardly long shape (the Paris Psalter is 52,6 cm long and only 18,6 cm wide) and a strange “open-topped a, looking rather like a u” at the end of some lines. Emms identified the same features in a late 10th-century manuscript of the Benedictine Rule from Canterbury (London, British Library, Harley 5431) and suggested this manuscript may have inspired Wulfwine:

The proposed localisation of Wulfwine in Canterbury is strengthened by the fact that some of the illustrations in the Paris Psalter resemble those of the Harley Psalter made in Canterbury (the Harley Psalter, in turn, was inspired by the ninth-century Utrecht Psalter, then in Canterbury). The illustrations of Psalm 4:6 (Offer up the sacrifice of justice) in both manuscripts are, indeed, similar:

Emms (1999) was even able to locate a monk named Wulfwine in a late 11th-century necrology of the monastic community of St. Augustine’s, Canterbury:

Could this Wulfwine ‘the scribe’ whose death was recorded in the late 11th-century Canterbury necrology really be the same person as scribe Wulfwine ‘the Lumpy’ who made the Paris Psalter and was inspired by at least two Canterbury manuscripts? As with the identification of Alfred the Great as the author of the prose translations, the evidence concerning the identity of the scribe Wulfwine is solely circumstantial, but the details do add up!

Filling the gaps: Some illustrations from the Paris Psalter

In producing the pages of the Paris Psalter, Wulfwine ‘the Lumpy’ had one particular problem: the Old English prose translation in the right hand column was often longer than the Latin original in the left-hand column. Consequently, the left-hand column often featured some gaps. Initially, Wulfwine tried to fill these gaps with illustrations; later, he tried to fix the problem by wrapping the Latin text in an awkward way; until he finally gave up on the idea of filling the left-hand column and simply let the gaps stand.

That Wulfwine eventually abandoned the idea of filling the gaps with illustrations is to be regretted. While some of his illustrations match the well-known Harley Psalter, others are unique to the Paris Psalter and shed an interesting light on how an Anglo-Saxon interpreted these Psalm texts. Below, I provide my personal top five of the fabulous illustrations of the Paris Psalter.

5) “Coochee coochee coo”

Here, the artist has literally illustrated the Old English translation of Psalm 3:4: “þu ahefst upp min heafod” [you raise up my head]. I like how God gently seems to tickle the Psalmist under his beard.

4) That moment when God thinks your beard needs trimming

This illustration shows a rather less cute interaction between God and a human being. The bearded figure, in this case, must be one of the “yfelwillenda” [those who want evil] or the “unrihtwisan” [the unjust], and God is intending to use his mega-scissors to remove this person from his sight.

3) Lion got your soul?

Another literal rendition: the lion trampling this young man is the enemy getting hold of a soul. Wulfwine here took inspiration from the Harley Psalter (or the Utrecht Psalter itself):

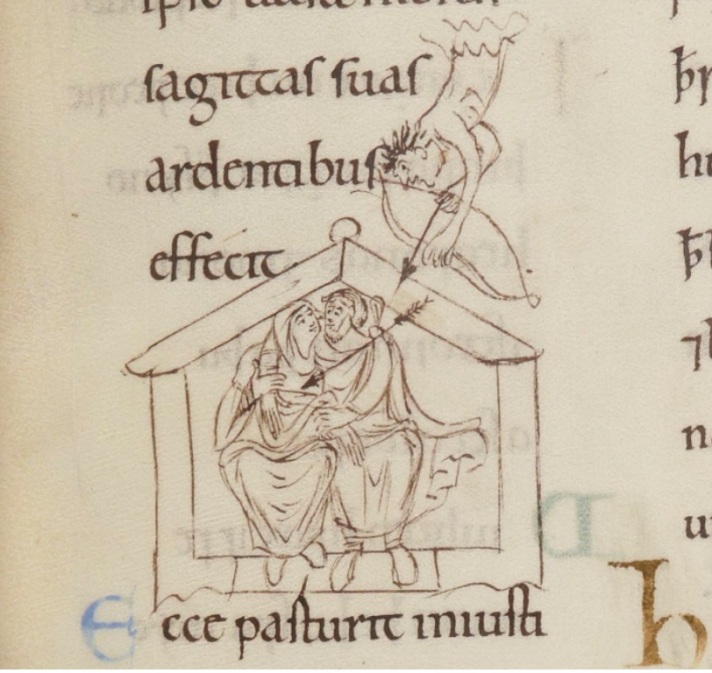

2) Struck by Cupid’s..err Satan’s arrows!

A depiction of Ps. 7:14 (he hath made ready his arrows for them that burn) shows Satan shooting an arrow into the heart of the female part of a lovers’ couple. Apparently, the couple had wild plans in their little love nest; note how the lovers are reaching between each other’s legs with their hands.

1) What will happen to the evil-doers

Psalm 5:7 (Thou hatest all the workers of iniquity: thou wilt destroy all that speak a lie. The bloody and the deceitful man the Lord will abhor) makes clear that God does not like those who commit evil acts and will seek to destroy them. The artist has depicted the first part of Psalm 5:7 as follows:

These evil-doers and liars are not, as I first thought, taking a trip in a boat; they are, in fact, in the mouth of Hell (see its little eye-ball on the left).

The illustration of the second part of Psalm 5:7 (…The bloody and the deceitful man the Lord will abhor) is more spectacular:

‘If you pull my hair, I will stab your groin!’: Ouch!!!

If you liked the blog post, you may also enjoy:

- A medieval manuscript ransomed from Vikings: The Stockholm Codex Aureus

- An Anglo-Saxon comic book collector: Cuthwine and the Carmen Paschale

- The Marvels of the East: An early medieval Pokédex

- The Illustrated Old English Hexateuch: An early medieval picture book

Works refered to:

- Emms, Richard. 1999. The scribe of the Paris Psalter. Anglo-Saxon England 28 (1999): 179-183.

- O’Neill, Patrick. 2001. King Alfred’s Old English Prose Translation of the First Fifty Psalms (Medieval Academy of America, 2001)

Reblogged this on pmayhew53.

LikeLike

Where might I find a translation of Alfred’s introduction to his version of Psalm 32:1-2? Thank you.

LikeLike

By far the best translation of the Old English Psalms is by Patrick P. O’Neill (Harvard, 2016). His translation of Alfred’s introduction reads: “David sang this thirty-second psalm, praising the Lord and thanking him because he so miraculously freed him from all his troubles, and so honorably appointed him over his kingdom; and also he urged all people to thank God for all the good things which he did for them; and he prophesied also about Hezekiah, that he was destined to do the same, whenever he was freed from his difficulties; and he prophesied also about Christ, that after his resurrection he would teach the same thing to all people.” (p. 107). The translation of Psalm 32:1-2 reads “Rejoice, you just, in God’s gifts; it is truly fitting that all rightly disposed people praise him simultaneously. Praise him with harps and on the ten-stringed lyre.” (p. 107)

LikeLike