This blog post looks at how Bede’s famous parable of the sparrow was reused in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries.

Bede’s sparrow

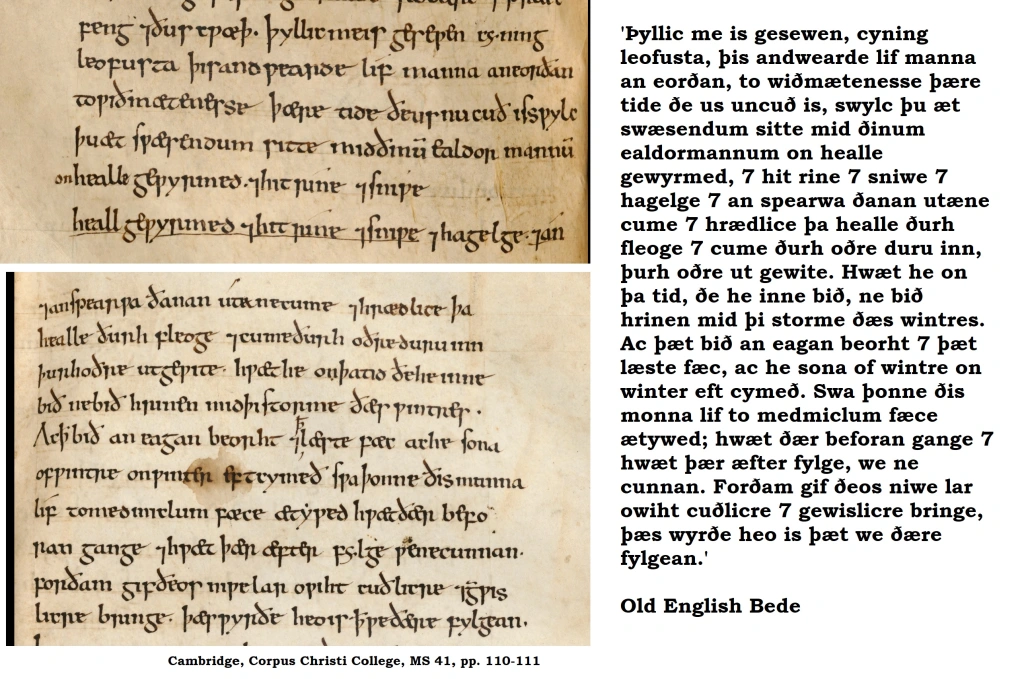

Bede’s famous parable of the sparrow is a common text in many introductory courses of Old English. It is found in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731), when he discusses how King Edwin of Northumbria was converted to Christianity in the year 627. In Bede’s story, one of Edwin’s counsellors compares the life of a pagan to the flight of a sparrow through the king’s warm hall. Here is the Old English version of the counsellor’s speech, from an 11th-century manuscript:

It seems to me thus, dearest king, that this present life of men on earth, in comparison to the time that is unknown to us, [is] as if you were sitting at your dinner tables with your noblemen, warmed in the hall, and it rained and it snowed and it hailed and one sparrow came from outside and quickly flew through the hall and it came in through one door and went out through the other. Lo! During the time that he was inside, he was not touched by the storm of the winter. But that is the blink of an eye and the least amount of time, but he immediately comes from winter into winter again. So then this life of men appears for a short amount of time; what came before or what follows after, we do not know. Therefore, if this new lore brings anything more certain and more wise, it is worthy of that that we follow it.’

Bede’s image is simple but effective: paganism, according to Bede, does not account for Creation or the Afterlife – the life of a pagan, therefore, resembles the flight of a sparrow through the king’s hall: it comes from the cold and dark winter, spends some brief time in the warm and pleasant hall and then it returns to the cold and dark winter. Since Christianity does give clarity about what came before and what came after, it must be better. Arguably, Bede is misrepresenting whatever pre-Christian faith Edwin of Northumbria and his counsellors adhered to, but that does not make the image less effective. Indeed, while Bede notes that the sparrow’s flight is over in the blink of an eye, Bede’s story reverberates until this present day.

William Wordsworth’s “Persuasion” (1822)

Bede’s parable of the sparrow was reiterated in sonnet-form by William Wordsworth (1770-1850) in his Ecclesiastical Sonnets (1822), a series of 132 poems narrating the history of Christianity, from its arrival in Britain to Wordsworth’s own days. In Wordsworth’s sixteenth sonnet “Persuasion”, Bede’s sparrow represents the human soul:

Man’s life is like a Sparrow, mighty King!

William Wordsworth, “Persuasion” (1822) – source

That—while at banquet with your Chiefs you sit

Housed near a blazing fire—is seen to flit

Safe from the wintry tempest. Fluttering,

Here did it enter; there, on hasty wing,

Flies out, and passes on from cold to cold;

But whence it came we know not, nor behold

Whither it goes. Even such, that transient Thing,

The human Soul; not utterly unknown

While in the Body lodged, her warm abode;

But from what world She came, what woe or weal

On her departure waits, no tongue hath shown;

This mystery if the Stranger can reveal,

His be a welcome cordially bestowed!

In Wordsworth’s version, the king’s warm hall represents the human body, while the sparrow is the human soul. This interpretation of the sparrow may well have been what Bede intended and, at any rate, has an analogue in Psalm 123:7 (“Our soul hath been delivered as a sparrow out of the snare of the fowlers”).

Edwin Morgan’s “Grendel” (1976-1981)

Edwin Morgan (1920-2010) put the image of Bede’s sparrow on its head in his monologue poem “Grendel”. In this poem, we get the monster Grendel’s pespective on the hall Heorot (the Old English poem Beowulf tells us that Grendel decided to attack the hall, because he was distraught by the noise of merry-making Danes in the hall). In contrast to the warmth and pleasantness that both Bede and Wordsworth ascribed to the hall, Morgan’s Grendel describes the hall as a horrible place that the sparrow is glad to leave:

Who would be a man? Who would be the winter sparrow

A passage from Edwin Morgan’s “Grendel”

that flies at night by mistake into a lighted hall

and flutters the length of it in zigzag panic,

dazed and terrified by the heat and noise and smoke,

the drink-fumes and the oaths, the guttering flames,

feast-bones thrown to a snarl of wolfhounds,

flash of swords in sodden sorry quarrels,

till at last he sees the other door

and skims out in relief and joy

into the stormy dark?

Bede’s warm and cosy hall are nowehere to be seen in this version of the sparrow’s flight! In this passage, as elsewhere in Morgan’s poem, Grendel’s disgust over human society shines through. This bleak view of humanity may also explain the two opening lines of the poem: “It is being nearly human / gives me this spectacular darkness”.

Morgan was well acquainted with Old English poetry; he made a translation of the original Beowulf and also a number of poem collected under the heading “From the Anglo-Saxon” in his Dies Irae (1952).

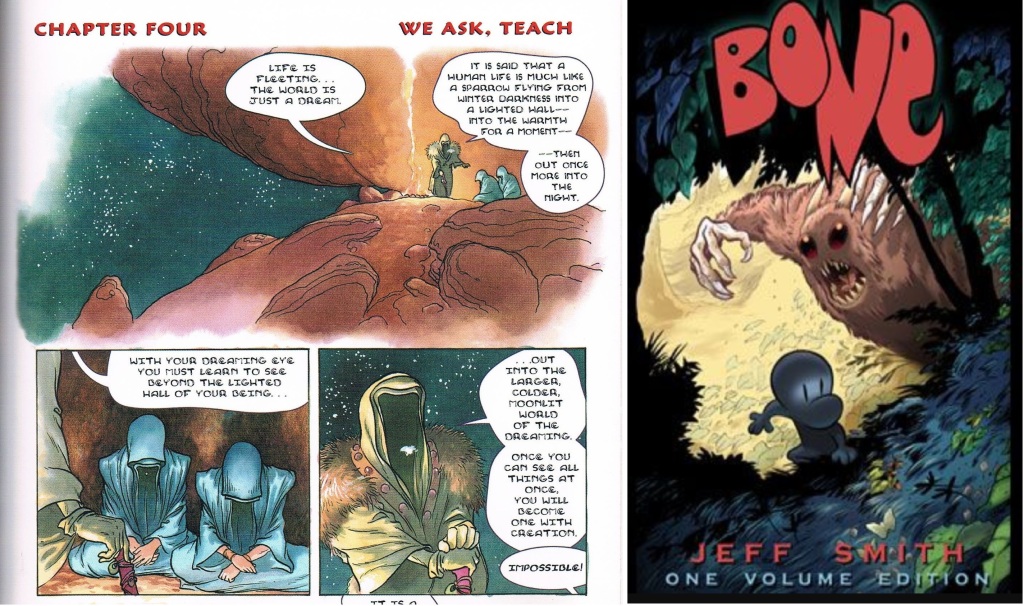

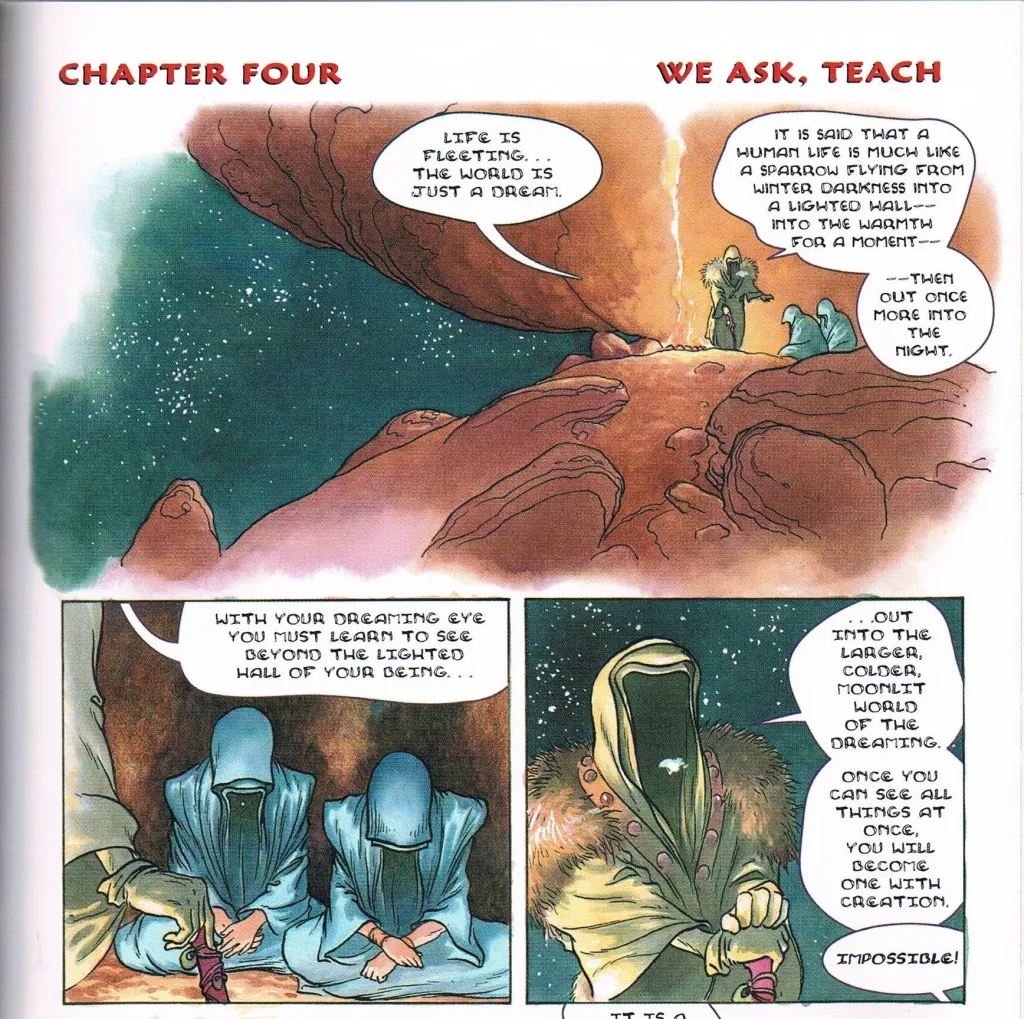

Jeff Smith’s BONE (1991-2004)

I am a fan of Jeff Smith’s epic comic book saga BONE (1991-2004). The series has received multiple awards and was named one of the ten greatest graphic novels of all time by TIME magazine, which described it as: “As sweeping as the Lord of the Rings cycle, but much funnier”.

Here is an image taken from the prequel volume Rose (2000-2002) and shows the ‘headmaster of the Venu’ (the hooded figure) explaining how ‘the dreaming’ (a sort of spirit world where everyone comes from and to which everyone must one day return) works.

In the BONE Companion (2016), Stephen Weiner explains that the dreaming is based on the Aboriginal concept of the ‘Dreamtime’. From the way the headmaster explains the concept, however, we can also see some influence from Bede! In the headmaster’s simile, the hall stands once more for human life and the cold outside of winter encompasses everything beyond this present life.

To conclude, while the sparrow in Bede’s imagination only spent a brief moment in the hall, Bede’s image has certainly stood the test of time!

If you liked this blog post, you can sign up for regular updates and/or read the following posts:

- Medieval manuscripts in modern media: Anglo-Saxon manuscripts spotted in Vikings, The Last Kingdom and Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla.

- Anglo-Saxon props: Three TV series and films that use early medieval objects