The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a fascinating collection of Old English annals that survives in multiple manuscripts and manuscript fragments. This blog post demonstrates that the manuscripts show a fascinating variety even in those annals for which there was little to nothing to report.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: From Julius Caesar to William the Conqueror and beyond

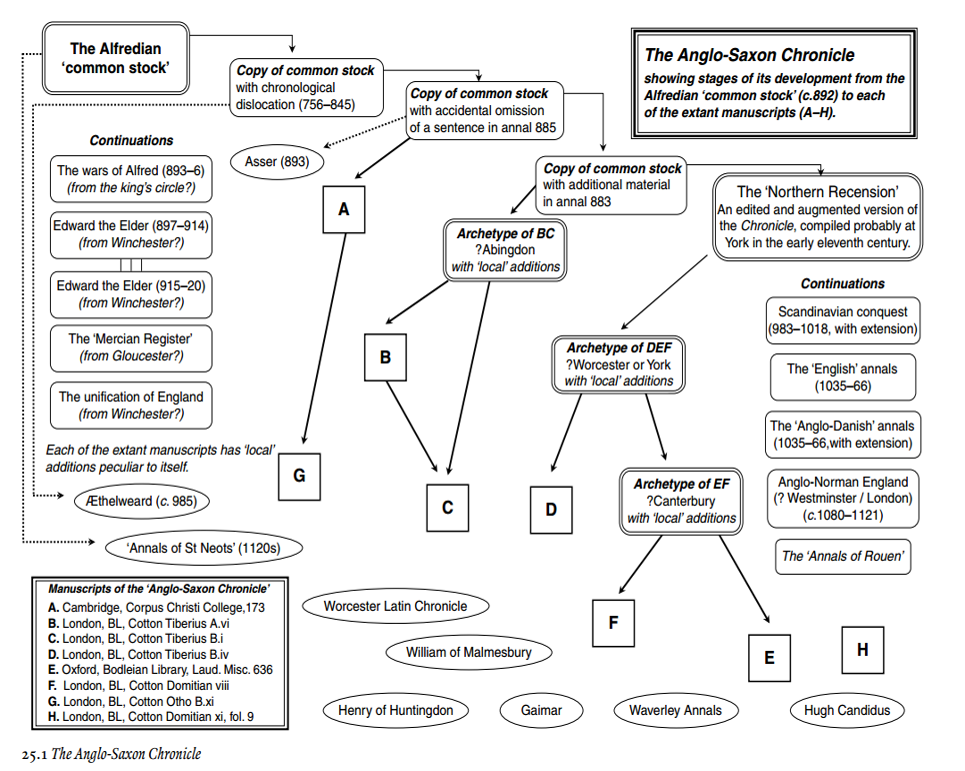

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle starts its history of England in the year 60 BC, with the failed invasion of Britain by Julius Caesar. Annals that follow report on the arrival of the Germanic tribes, led by Hengest and Horsa, genealogies of various Anglo-Saxon kings and the battles between the Vikings and Alfred the Great. It was probably at the behest of Alfred that the first stretch of annals (from 60 BC to 892 AD) was composed and this ‘Common Stock’ is found in all extant (complete) manuscripts of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. However, each manuscript version of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells a unique story, having been copied in different places and at different times, leading to scribes adding, altering and omitting information in the transmission of the text. One manuscript (the Peterborough Chronicle) continues the annals up until the year 1154. The relationship between the manuscripts and related (Latin) chronicles is highly complex as the following diagram from a great article by Simon Keynes demonstrates:

The contents of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is fascinatingly varied, ranging from relatively dry information (this king died; that king died) to exciting heroic narrative (the story of Cynewulf and Cyneheard), impressive genealogies (often including the names of people from Germanic Legend) and actual Old English poetry (e.g., The Battle of Brunanburh). In previous blog posts, I have dealt with two remarkable events recorded in these Old English annals: #NotMyConqueror: Gytha and the Anglo-Saxon Women’s March against William the Conqueror and An Anglo-Saxon Anecdote: The Battle of the Birds, 671. In this blog post, I want to call attention to the years 190 to 381, during which, according to one manuscript of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, literally nothing happened.

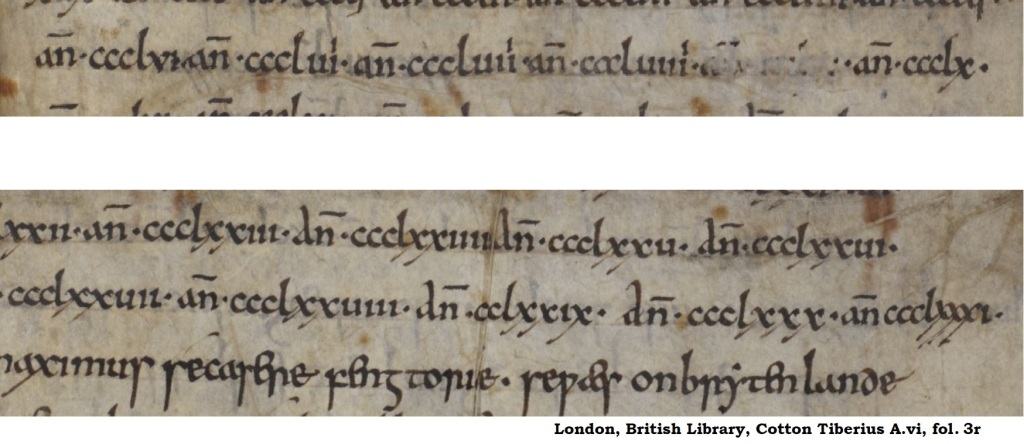

Manuscript B: Nothing to see here!

AN. CXC, AN. CXCI, AN. CXCII, AN. CXCIII, AN. CXCIIII, AN. CXCV, AN. CXCVI, etc. We have to admire the diligence of the scribe of MS B of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle who wrote these ‘entries’ for the years 190 to 381. Apparently, there was nothing to report for these years, but the scribe did feel that it was necessary to write out the full numbers and the abbreviations “AN.” for “anno” 191 times. This must have been a tiring task and we can see that the scribe actually noticed a mistake along the way: he had copied the year 356 twice and found out when he had reached 360. At this point, he went back to correct the second 356 to 357 by adding a little I above the last Roman numeral CCCLUI; he did the same for 358 and 359 and erased whatever stood between 359 and 360. That is dedication! Regardless, one mistake was left unnoticed: for the year 379 he accidentally left out a C [AN. CCCLXXUIII, AN. CCLXXIX, AN. CCCLXXXI], but can we really blame him?

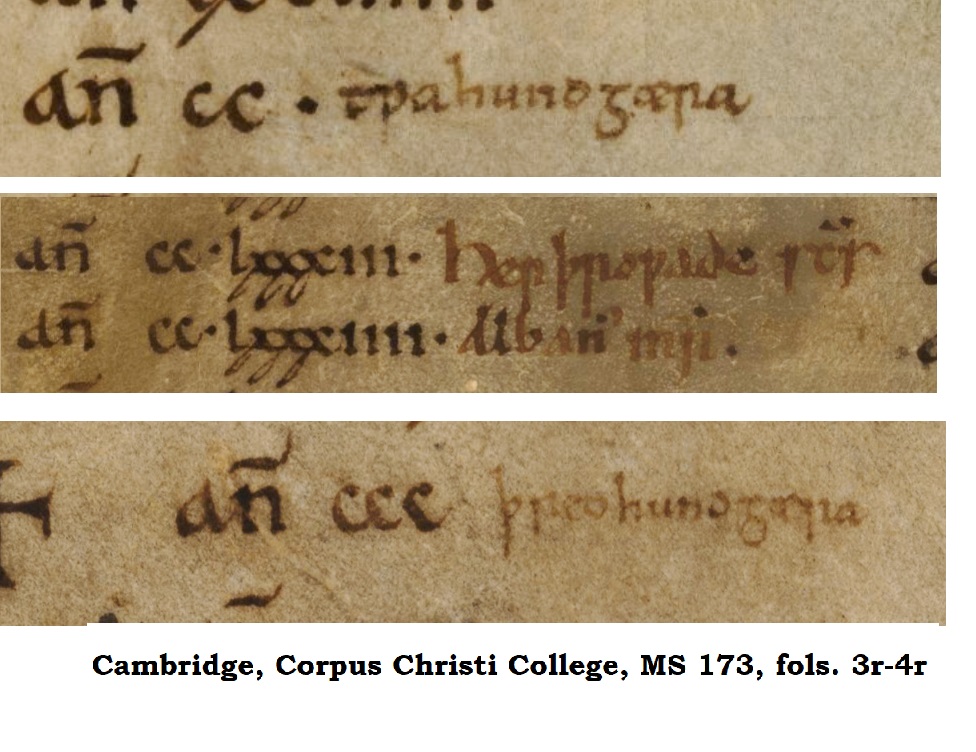

Manuscript A: Room for ‘exciting’ additions!

The same range of annals (190 to 381) looks a lot more impressive in the Parker Chronicle (manuscript A):

Admittedly, the way that the scribe of manuscript B handled this series of annals is more economical, but manuscript A at least allows for some room for potential additions. The additions that were made within the range 190 to 381, however, are not the most informative ones: for the year 200, someone added “twa hund gæra” [two hundred years] and for the year 300, the same person added “þreo hund gæra” [three hundred years] – great facts, guys! For the year 283, the death of St Alban is reported: “her þrowade sanctus Albanus martyr” [in this year, the martyr saint Alban suffered].

Manuscript C: Colour patterns!

Manuscript C follows Manuscript B in not reporting anything of note in the range 190 to 381 and, instead, just lists all the years + AN. To make the page still somewhat exciting, the scribe uses a different colour ink for every line:

But even the neat colour patterning did not withhold this scribe from making an error: the pattern breaks when he accidentally copies out two lines in red, which he then follows up by two lines in black, before returning to one line of red:

Manuscript D: Parchment to spare

Whoever was responsible for the layout of manuscript D of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle had parchment to spare: rather than writing out all the years consecutively, like MSS B and C, or writing out the years in two columns like manuscrpt A, Manuscript D gives the years in one column. As a result, the range 190 to 260 alone already spans three pages. The next folios have been lost and they are replaced with 16th-century ‘supply-leaves’ (giving the text of folios that are now missing):

The sixteenth-century hand, belonging to John Jocelyn (1529-1603), seems to have taken some effort to reproduce all the year numbers, although he gives up at the year 286, for which he now gives the death of St. Alban “Her ðrowade santus Albanus martyr”.

Note also the original scribes colour patterning, using blue and red ink.

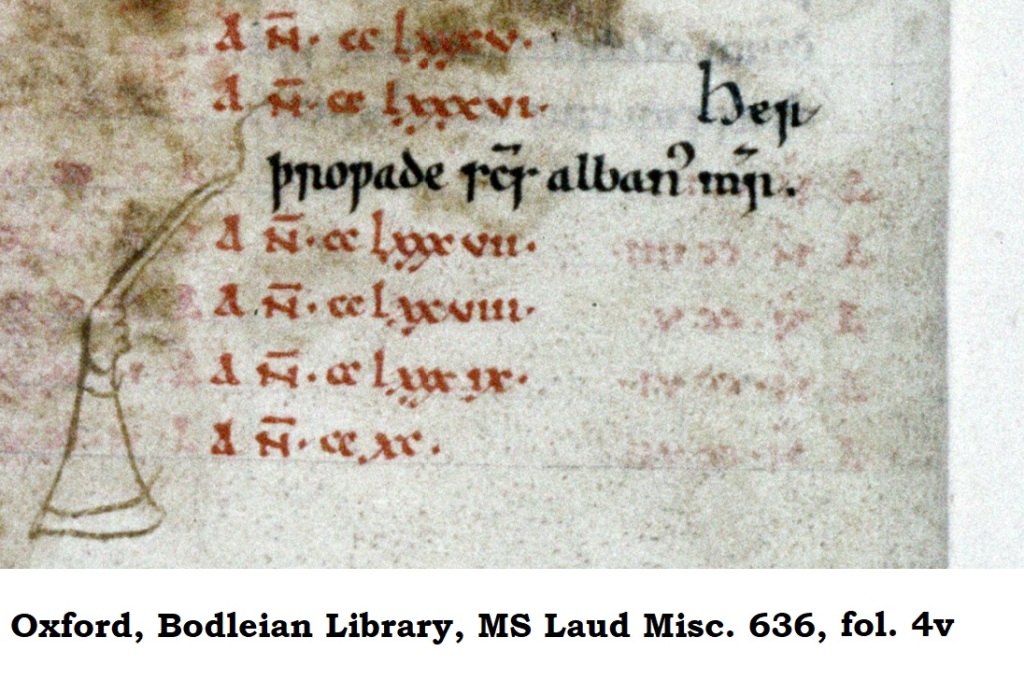

Manuscript E: A creepy little hand

Manuscript E brings us back to the two-column layout of manuscript A. This is combined with different colour ink for the year numbers and the textual entries. It seems as if this copy of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle had some more things to say for the years 190 to 381, but they still look like two boring centuries:

Clearly, the death of St Alban (here in the year 286, as in Manuscript D, but unlike Manuscript A which had it down in 283) was considered the most important event, since it is called attention to by a little hand (manicula) with a creepily long and wavy index finger:

Manuscript F: The years are fading away!

There is not much to say about manuscript F of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle other than that its bilingual nature (it gives the text of the entries in Old English and Latin) did not affect the way that the year numbers are presented on the page – manuscript F follows B and C in writing the year numbers consecutively, even if this scribe did not bother to copy out the abbreviation “AN.” 191 times! Unfortunately, red ink was used for the year numbers and this has all but faded away. For the ‘textual entries’, the scribe used black ink, which means we can still read the entry for the death of St Alban, which, in this manuscript, appears to have taken place in the year 287, unless the scribe copied the year 286 twice.

Looking back at this blog post, we can draw two conclusions:

1) Even for stretches of time in which almost nothing happened, the manuscripts of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicleshow a fascinating diversity.

2) Nobody knew exactly when St Alban died. Manuscript A has 283; D and E opt for 286 and F seems to put it at 287. Wikipedia (The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of the modern age) suggests the death of St Alban either happened in c. 251 or 304 – so I guess we still don’t know.

If you liked this blog post, consider signing up for regular blog updates and/or check out these posts:

- Anglo-Saxon gift horses: Equine gifts in early medieval England

- Half-assed humanoids: Centaurs in early medieval England

- Sitting down in early medieval England: A catalogue of Anglo-Saxon chairs