TV series and video games set in early medieval England often include little historical details in the background to add to a sense of realism and historical accuracy. In a previous blog post, I discussed the use of such ‘Anglo-Saxon props’ in the The Last Kingdom (BBC/Netflix; 2015-) , Merlin (BBC/Netflix; 2008-2012) and Ivanhoe (MGM; 1952) (see: Anglo-Saxon props: Three TV series and films that use early medieval objects). In this blog post, I discuss the appearance of Anglo-Saxon manuscripts in Vikings (History Channel/Netflix; 2013-), The Last Kingdom and Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla (Ubisoft; 2020). This blog post may contain minor spoilers…

Vikings (History Channel/Netflix; 2013-): Eighth-century manuscripts in a ninth-century scriptorium

With its focus on legendary Viking leader Ragnar Lothbrok and his sons, History Channel’s Vikings spends a good amount of screentime on early medieval England. In particular, much of the first five series of the show centre on the kingdom of Wessex, ruled by King Ecgberht (r. 825-839) and his son Æthelwulf. In the fourth series, Princess Judith (married to Æthelwulf) learns the art of manuscript illumination and is seen in two episodes practising her newly acquired art.

In episode, 2 of series 4, Judith is seen making the mid-eighth-century Vespasian Psalter in King Ecgberht’s mid-ninth-century scriptorium:

The Vespasian Psalter is a beautiful, glossed manuscript that I have discussed earlier here: Reading between the lines in early medieval England: Old English interlinear glosses.

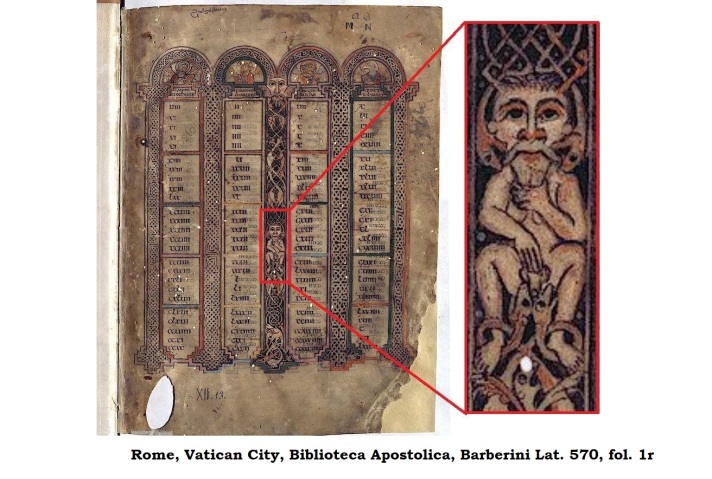

In the next episode, Judith is seen at work on the portrait of Matthew the Evangelist in the Barberini Gospels (in actuality made in 8th-century England):

The portrait of Matthew is a prudent choice for the not-so-prudent Judith, since the Barberini Gospels also feature a rather obscene image of a naked man ‘pulling his beard’ (I discuss this image and other obscene art from the period here: Anglo-Saxon obscenities: Explicit art from early medieval England):

The Last Kingdom (BBC/Netflix, 2015-): A ninth-century chronicle and pardon with eleventh-century features

The first three series of The Last Kingdom are set during the reign of Alfred the Great (d. 899). In the third series, Alfred is nearing the end of his life and is concerned for his legacy; in various episodes, references are made to a chronicle that Alfred has ordered to be made for the purpose of securing how he will be remembered. As Alfred explains it, this chronicle would record his deeds and make sure that hundred years later people will still remember him and his idea for England. The Last Kingdom‘s ‘Alfred chronicle’ seems to be a reference to the so-called Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the first compilation of which was indeed begun during Alfred’s reign and shows a rather partisan view of Alfred’s Wessex.

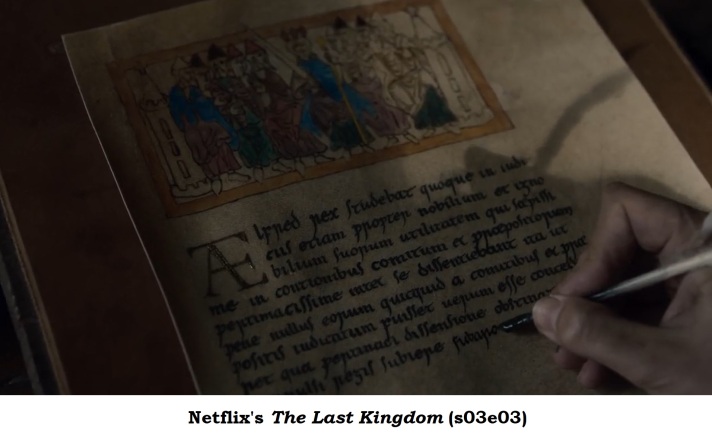

In episode three, the chronicle is first introduced and we are given a glimpse at one of the manuscript pages:

The text of the manuscript is in Latin, suggesting that we are not dealing with the Old English Anglo-Saxon Chronicle; instead this entire page (with the exception of the first two words “Ælfred rex”) appears to have been drawn from Asser’s Life of Alfred (available here, the manuscript text “Studebat quoque in iudiciis…” is from chapter 106, the very last part of Asser’s text). This is a good choice, since this biography of Alfred the Great was indeed written during Alfred’s lifetime by the Welsh bishop Asser (who made an appearance in the last three episodes of the first series of The Last Kingdom, but he has since disappeared).

The illustration, however, strikes as odd: it is from an eleventh-century manuscript known as the Illustrated Old English Hexateuch:

The Old English Illustrated Hexateuch is a fascinating manuscript: it has an Old English translation and paraphrase of the first six books of the Bible and the text is interspersed with illustrations (see: The Illustrated Old English Hexateuch: An early medieval picture book). The image used in The Last Kingdom’s ‘Alfred chronicle’ is based on the Hexateuch’s depiction of Genesis 40:22, showing the Pharoah, surrounded by his advisors. hanging his chief baker. The hanged baker appears to have been cropped out of the picture in The Last Kingdom – perhaps Alfred didn’t want to be reminded of his own baking skills!

Alfred spends much of the third series brooding over his chronicle in his scriptorium and, in episode seven, we are given a look at another page. This page shows a boat, filled with Vikings and horses, as well as a bird pecking at an impaled head.

The Latin text on the pages is, once again, drawn from Asser’s Life of Alfred (chapter 67 this time, describing how Alfred defeated Vikings in Kent, so again a good textual fit!). The image is a mash-up of Noah’s ark from the Illustrated Old English Hexateuch and a Norman boat on the Bayeux Tapestry:

The boat in the Alfred chronicle seemes to be inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry for its inclusion of both men and horses (as well as its sail). With the Hexateuch’s Ark of Noah, the Viking boat in the Alfred chronicle shares not only the animal-like boat-ends, but also the intriguing feature of an impaled head on a stick (if you are interested in why there is an impaled head on Noah’s ark, read Heads on sticks: Decapitation and impalement in early medieval England).

In episode 9 of the third series, Uhtred and Alfred meet up in the scriptorium and a number of pages from the Alfred Chronicle are shown lying side by side. The Latin text is again from Asser and the drawings are, again, based on the eleventh-century Illustrated Old English Hexateuch:

In the same episode, Alfred writes a pardon for Uhtred, forgiving him his trespasses. The pardon is written in Old English and I have been able to decipher almost all of it; I provide my tentative transcription and translation below:

HER SWUTELAÞ on þis

gewrit þæt ÆLFRED cyn

ing westseaxna …. …

þone fleman UCTREDE …

his sawle VII nihtlang ær þæra

haligra mæssan. Þis wæs ge

don in þam cynelican byrig

on þære stowe ðe is genæm

ned Wintanceaster on Ælfred

es cyninges gewitnesse 7 Uc

tredes ealdormannes 7 hæbbe

he godes curs þe þis æfre

undo a on ecnysse. PAX CHR[IST]I

NOBISCUM

ælfred rex[Here it is revealed in this writing that Ælfred, king of the Westsaxons … the fugitive Uhtred … his soul seven night’s long before the holy mass. This was done in the royal fortification in the place that is named Winchester by witness of Alfred the king and of Uhtred the nobleman and may he have God’s curse always in eternity who should ever undo this. Peace of Christ with us.

King Alfred]

The first part of this text, which mentions the TV series’s character Uhtred (with its Anglo-Saxon spelling Uctred), seems to have been tailor-made for the show, but the last part of the text “hæbbe he godes curs þe þis æfre undo a on ecnysse” [may he have God’s curse always in eternity who should ever undo this] is a common curse-type, found in many legally binding documents from early medieval England. These curses prevent anyone from altering the document and undoing what it has stated.

Intriguingly, the curse that Alfred uses has an exact parallel in a so-called manumission: a statement for the release of a slave. This manumission was added to the Leofric Missal (digitized here) at the end of the eleventh century,:

Her kyð on þisse bec þæt æilgyuu gode alysde hig 7 dunna 7 heora ofspring, æt mangode to XIII mancson 7 æignulf portgerefa 7 Godric gupa namon þæt toll on manlefes gewittnisse, 7 on leowerdes healta, 7 on leowines his broþor, 7 on ælfrices maphappes, 7 on sweignis scyldwirhta. And hæbbe he godes curs, þe þis æfre undo a on ecnysse, Amen.

[Here is made known in this book that Æilgyvu ‘the Good’ released Hig and Dunna and their offspring from Manegot for 13 mancuses and Æignulf the portreeve and Godric Gupa took the payment by witness of Manlef and Leowerd Healta and his brother Leowine and Ælfric Maphapp, and Sweign the shieldmaker. And may he have God’s curse always in eternity who should ever undo this. Amen]

Given that curses of this type are mostly found in manumissions, it seems like a suitable way for Alfred to end his pardon by which he ‘releases’ his noble and loyal follower and henchman.

Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla (2020): A pastoral manuscript turned into declaration of war

On the 30th of April of 2020, the cinematic trailer for the video game Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla came out. I was alerted to its presence by a student who noted that Alfred the Great made an appearance in the trailer. I watched the trailer and immediately noticed some interesting historical details, which I promptly shared on Twitter on the same day:

The last detail deserves an extended treatment here: Alfred signs a declaration of war, using the decidedly un-Old English word “WAR”; the rest of the text is Old English and I soon recognized the text and the manuscript it was taken from as a work that is indeed attributed to Alfred the Great himself.

It turns out to be a manuscript (digitized here) that is contemporary to Alfred (dated c. 890-897) and contains a translation of Gregory the Great’s Cura Pastoralis [Pastoral Care] into Old English. The translation is preceded by a preface by Alfred the Great himself, in which he writes that he himself was in fact responsible for this translation (with the aid of some teachers); the text on the Assassin’s Creed declaration is from that preface.

The Cura Pastoralis is a work on the pastoral responsibilities of the clergy (i.e. how churchmen should take care of their flock) so it seems odd that Assassin’s Creed‘s Alfred would use part of this text to declare war on the Vikings, but at least the manuscript -and- the text are both a chronological fit, which, as we have seen, is only rarely the case!

If you liked this blog post, consider following this blog (button in the menu on the right) and/or enjoy the following posts as well:

- Anglo-Saxon props: Three TV series and films that use early medieval objects

- Arseling: A Word Coined by Alfred the Great?

- Splitting Anglo-Saxon Hairs: Cuthbert’s Comb