In the early Middle Ages, dwarfs appear to have been associated with a medical condition. That is, the Old English word for dwarf, dweorg, could also denote “fever, perhaps high fever with delirium and convulsions” [Dictionary of Old English, s.v. dweorg]. As a result, the term dweorg pops up in various remedies that are intended to rid the patient of their dwarf and/or fever; here are five sure ways to get rid of those short-statured, bearded individuals!

1. Write some symbols! Old English charms

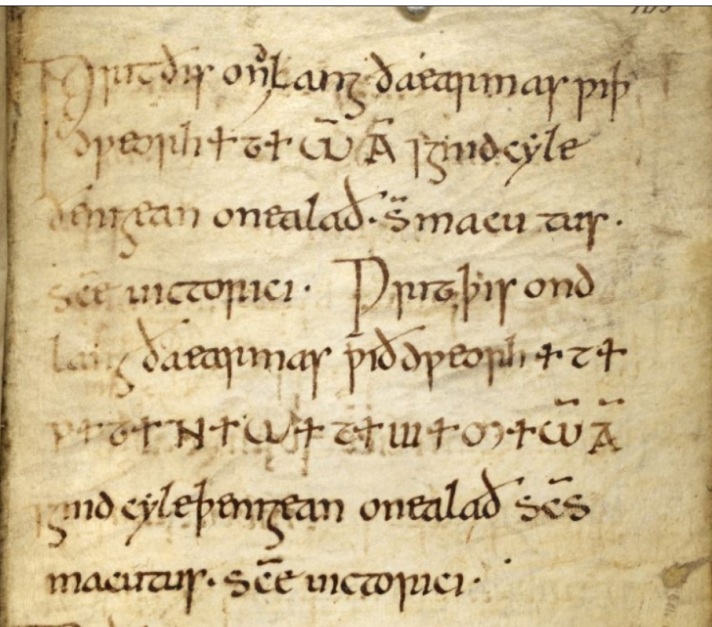

The Anglo-Saxon medico-magical collection known as the Lacnunga (surviving in a 10th/11th-century manuscript) features a number of remedies against a dwarf. Two of these involve writing a series of symbols (crosses and Greek letters) along one’s arms, followed by the mixing of great celandine with ale and calling upon two saints (Macutus and Victoricus):

Writ ðis ondlang da earmas wiþ dweorh, … 7 gnid cyleðenigean on ealað, sanctus macutus sancte uictorici.

Writ þis ondlang ða earmas wið dweorh, … 7 gnid cyleþenigean on ealað, sanctus macutus, sancte uictorici.

[Write this along the arms against a dwarf … and mix celandine in ale, saint Macuturs, Saint Victoricus.

Write this along the arms against a dwarf … and mix celandine in ale, saint Macuturs, Saint Victoricus.]

The notion that writing symbols may alleviate one from a dwarf is also found in one other Old English charm. On the flyleaf of an eleventh-century manuscript, an Anglo-Saxon scribe wrote a string of Christian gobbledegook (“thebal guttatim aurum et thus de. + albra Iesus + alabra Iesus + Galabra Iesus +”), followed by this Old English instruction:

Wið þone dworh on .iii. oflætan writ.

THEBAL GUTTA

[Against the dwarf, write on three wafers:

THEBAL GUTTA]

THEBAL GUTTA seems to be pure mumbo-jumbo (akin to abracadabra); the use of wafers is interesting, since these are also used in the most famous Old English charm which is simply entitled “Wid dweorh” [against a dwarf].

2. Summon its sister! An Old English charm against a dwarf

This charm, found among the Lacnunga, instructs one to take seven “lytle oflætan swylce man mid ofrað” [little wafers like the ones people use to worship; i.e. the Host] and write down the names of seven saints (Maximianus, Malcus, Johannes, Martinianus, Dionysius, Constantinus and Serafion – the names of the Christian saints collectively known as the Seven Sleepers). The charm further instructs that a virgin must hang these wafers around the neck of the patient and that you are to sing a particular song, “ærest on þæt wynstre eare, þænne on þæt swiðre eare, þænne bufan þæs mannes moldan” [first into the left ear, then into the right ear, then on top of the patient’s head]. This ritual is to be repeated for three days in a row: “Do man swa þry dagas him bið sona sel.” [Do this for three days and then he will immediately be well].

The charm also provides the text of the song you are supposed to sing. This song is rather enigmatic, but the usual interpretation is as follows: the first four lines describe the cause of the patient’s complaints: a small being [the dwarf] has put reins over the patient and has started to ride them as if they were a horse; the next lines describe the cure: the sister of the dwarf is summoned and she puts an end to the patient’s ordeal and swears oaths that it shall never happen again.

Her com in gangan, in spiderwiht,

hæfde him his haman on handa, cwæð þæt þu his hæncgest wære,

legde þe his teage an sweoran. Ongunnan him of þæm lande liþan;

sona swa hy of þæm lande coman, þa ongunnan him ða liþu colian.

þa com in gangan dweores sweostar;

þa geændade heo and aðas swor

ðæt næfre þis ðæm adlegan derian ne moste,

ne þæm þe þis galdor begytan mihte,

oððe þe þis galdor ongalan cuþe.Amen. Fiað.

[Here came a spider-creature crawling in;

His web was a harness held in his hand.

Stalking, he said that you were his steed.

Then he threw his net around your neck,

Reining you in. Then they both began

To rise from the land, spring fromthe earth.

As they leapt up, their limbs grew cool.

Then the spider-dwarf’s sister jumped in,

Ending it all by swearing these oaths:

No hurt should come to harm the sick,

No pain to the patient who receives the cure,

No harm to the one who sings this charm.Amen. Let it be done. ] (Trans. Williamson 2017, p. 1075)

This charm’s effectiveness seems to rely on the combination of pagan Germanic, magical elements (the dwarf as a cause for the disease; its sister swearing oaths; a complex singing ritual involving a virgin) and Christian elements (the Host; names of Christian saints; the use of “Amen”) – this is a phenomenon often referred to as syncretism (the blending of two cultures).

3. Carve some runes! The Dunton plaque and Odin’s skull

Discovered as recently as 2015, a lead plaque dated to the 8th to 11th centuries features a very interesting runic inscription in Old English: “DEAD IS DWERG”. The inscription on this ‘Dunton plaque’ is easily translated to “The dwarf is dead” and may have worked in a similar manner to the Old English charms above. The act of writing the runes was part of a healing procedure; rather than a combination of Greek letters and Christian crosses or gobbledegook (THEBAL GUTTA!), the runic inscription is straightforward: the dwarf/fever is dead and gone. The hole in the plaque may indicae that it could be worn as a talisman (like the seven wafers used in the charm “Wið dweorh”).

John Hines (2019) has pointed out that this runic inscription has an interesting Scandinavian analogue in the Ribe skull fragment, dating to the early 8th century. Like the plaque, this skull fragment has a runic inscription and a hole suggesting it could potentially have been worn as a talisman:

ᚢᛚᚠᚢᛦᚼᚢᚴᚢᚦᛁᚾᚼᚢᚴᚺᚢᛏᛁᚢᛦ ᚺᛁᚼᛚᛒᛒᚢᚱᛁᛁᛋᚢᛁᚦᛦ ᚦᚼᛁᛗᚼᚢᛁᚼᚱᚴᛁᚼᚢᚴᛏᚢᛁᚱᚴᚢᚾᛁᚾ ᛒᚢᚢᚱ

Ulfr auk Ōðinn auk Hō-tiur. Hjalp buri es viðr þæima værki. Auk dverg unninn. Bōurr.

[Ulfr and Odin and High-tiur. Buri is help against this pain. And the dwarf (is) overcome. Bóurr.] (edition and translation from Schulte 2006, see also this Wikipedia article)

The interpretation of this skull fragment usually runs as follows: Buri/Bóurr is suffering from a fever/dwarf and this talisman is intended to alleviate Buri – it not only puts into writing the desired outcome (“the dwarf is overcome”), it also calls upon the aid of the Germanic god Odin, a wolf (Ulfr; perhaps Fenrir) and “High-tiur” (who may be the Germanic god Tyr). With this appeal to supernatural forces, this skull fragment resembles the invocations to Christian saints found in the Old English charms mentioned above.

4. Eat dog sh*t! A remedy from the Medicina de quadripedibus

The next dwarf expellant comes from the Old English translation of Medicina de quadripedibus, an early medieval medical compendium that outlines how various parts of four-legged animals may be used in remedies. Intriguingly, the text prescribes the use of a rather distasteful ingredient to get rid of a dwarf:

Dweorg onweg to donne, hwites hundes þost gecnucadne to duste 7 <gemengen> wið meolowe 7 to cicle abacen syle etan þam untruman men ær þær tide hys tocymes, <swa> on dæge swa on nihte swæþer hyt sy, his togan bið ðearle strang. 7 æfter þam he lytlað 7 onweg gewiteþ. (ed. De Vriend 1984, p. 266)

[To remove a dwarf, knead the excrement of a white dog to dust and mix it with milk and bake it into a small cake, give it the sick man to eat before the time of his [the dwarf’s?] coming, by day or by night whichever it is, his coming will be very strong and after that he grows small and will go away.]

It is not uncommon for Anglo-Saxon medical texts to prescribe waste products (excrement, urine, spit) to get rid of something – an example of sympathetic magic (for more examples, see: Early Medieval Magical Medicine: An Anglo-Saxon Trivia Quiz).

5. Kick it into the fire! Litr the dwarf’s fifteen seconds of fame in Snorri Sturluson’s Gylfaginning

Perhaps the most effective way of getting rid of a dwarf is demonstrated by the Germanic god Thor in Snorri Sturluson’s Gylfaginning (part of the Old Norse Prose Edda, c. 1220). After the beloved god Baldr died as a result of some trickery by Loki, the gods gather at Baldr’s funeral pyre, shedding tears of sadness. Snorri Sturluson paints a dramatic scene, with Baldr’s grief-stricken wife dying of sorrow, but then he follows this with a remarkable anecdote about Litr the dwarf:

Then was the body of Baldr borne out on shipboard; and when his wife, Nanna the daughter of Nep, saw that, straightway her heart burst with grief, and she died; she was borne to the pyre, and fire was kindled. Then Thor stood by and hallowed the pyre with Mjöllnir; and before his feet ran a certain dwarf which was named Litr; Thor kicked at him with his foot and thrust him into the fire, and he burned. (source)

This is, for as far as I know, the only appearance of Litr the dwarf in Scandinavian mythology. His fifteen seconds of fame demonstrate that the surest way of getting rid of a dwarf is to kick it into the fire; it is also a valuable lesson never to trip up a Germanic god!

- Cooked crow’s brains and other early medieval remedies for headaches from the Leiden Leechbook

- Early Medieval Magical Medicine: An Anglo-Saxon Trivia Quiz

- Creepy Crawlies in Early Medieval England: Anglo-Saxon Medicine and Minibeasts

- Anglo-Saxon aphrodisiacs: How to arouse someone from the early Middle Ages?–

Bibliography

- Hines, John. 2019. “Practical Runic Literacy in the Late Anglo-Saxon Period: Inscriptions on Lead Sheet.” In: Anglo-Saxon Micro-Texts, ed. Ursula Lenker & Lucia Kornexl, pp. 29-60. De Gruyter.

- Schulte, Michael. 2006. “The Transformation of the Older Fuþark: Number Magic, Runographic or Linguistic Principles?” Arkiv för nordisk filologi 121, pp. 41–74.

- de Vriend, Hubert Jan (Ed.). The Old English Herbarium and Medicina de Quadrupedibus. Oxford University Press.

- Williamson, C. (Trans.). 2017. The Complete Old English Poems. University of Pennsylvania Press.