The stomach of a hare, the excrements of a goat and the urine of a child – these are but a few of the awkward ingredients prescribed by the medical manuscript fragment known as the Leiden Leechbook. This ninth-century fragment, now in the Leiden University Library, is a unique witness to medical practice in the early Middle Ages and the multilingual nature of the documents from this period. This blog post outlines some of its remedies, its languages and its connection to Anglo-Saxon England.

How to cure a headache?

The first folio of the fragment contains a list of Latin remedies. As with other medical texts from the medieval period, this compilation starts with cures dealing with the head and then works its way down (in this case to the hair and eyes, then the text breaks off). To the modern reader, early medieval medicine presents a curious combination of herbal remedies and what might be called ‘magic’. The Leiden Leechbook’s remedies for headaches can serve as an illustration of this bewildering mix. The first three full remedies read as follows:

Item herbæ quæ in flumine super nascuntur subtilitær trita folia frontique illita mire purgationi capitis proficiunt.

Item lapilli in uentriculus pullorum hirundinum inuendi quamuis deuternos inueteratosque dolores remediant, habidi maximi albi, qui ne terram tangant erit cauendum.

Similiter noctuæ caput recens coctum et comestum deuternos labores sedare dicitur.

[Again: herbs which grow upon a river, (their) leaves chopped small and applied to the brow have a marvellous effect for clearing the head.

Again: stones found in the stomach of young swallows heal the pains, however old and persistent, chiefly white ones – care should be taken that they do not touch the earth.

Likewise: the head of an owl recently cooked, and eaten, alleviates so it is said persistent pains (in the head)] (ed. and trans. Falileyev & Owen, 2005)

While the first remedy is a sensible prescription to apply a herb to one’s forehead to alleviate a headache, the second one clearly features more ‘occult’ instructions. The third one is a clear example of so-called ‘sympathetic magic’ (“use like to treat like”): are you suffering from a head ache? Eat a head! (for similar examples of ‘sympathetic magic’ from the Middle Ages, see How to cook your dragon and a medieval cure for old age).

Other remedies for aching heads mentioned in the Leiden Leechbook include:

- The columbine plant

- Eating a coot

- Placing a small stone found on the side of a citygate on your head

- The root of plantain, picked before sunrise, bound around the head

- Smearing on the crushed seed of the elder tree

- Eating the brains of a cooked crow

- The nests of swallows, soaked in mud, applied to the forehead

- A drink of standing water out of which an ass or cow has drunk

Once more, we find the striking combination of purely botanical ingredients (plantain, columbine, seed of the elder tree) and more occult substances (the nest of swallows, a stone found on the side of a citygate). The instruction to eat the brains of a cooked crow to soothe aching brains is another case of sympathetic magic, as may be the advice to eat a coot (coots have a frontal shield on their foreheads).

One last cure for headache seems rather unhygienic:

Caprinus fimus aceto resolutus et front illitus mire succurrit.

[The excrement of goats, dissolved in vinegar and applied to the forehead, is of amazing benefit.] (ed. and trans. Falileyev & Owen, 2005)

One wonders how many long-sufferers of headaches walked around with acetic goat droppings on their foreheads in the early Middle Ages…

The Leiden Leechbook and the multilingual Middle Ages

The bifolium that is now known as the Leiden Leechbook was once used as a pastedown in another manuscript (i.e. it was pasted onto the board of another manuscript so as to hide its binding mechanisms). That manuscript, Leiden University Library, VLF 96, came from the famous abbey in Fleury, France, and, therefore, the Leiden Leechbook is generally assigned to the same abbey (see Bremmer & Dekker 2006; Falileyev & Owen, 2005) . Intriguingly, the Leiden Leechbook was certainly not written by a French monk: four hands are responisble for its texts and they all used an insular script (the kind used in the British Isles).

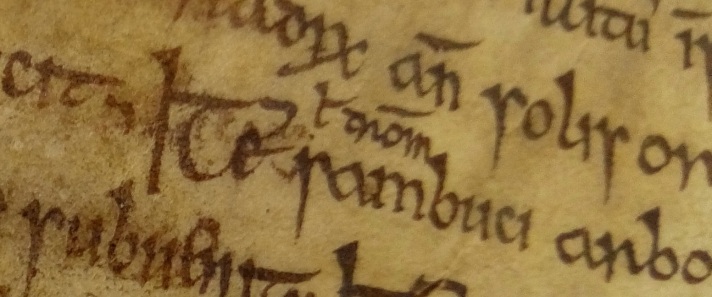

The languages in the Leiden Leechbook, too, suggest a multiregional background for the manuscript. Aside from Latin, there is one Old Irish gloss in the manuscript and some of its further remedies are written in a Brittonic language (possibly Breton or Cornish). The Old Irish gloss was added by the first scribe who copied the remedy for a headache that prescribed the use of crushed seeds of an elder tree. The Latin word sambuci ‘elder tree’ was glossed with the Old Irish word tromm ‘elder tree’:

The second folio of the Leiden Leechbook contains a different set of remedies, written in a mixture of Latin and a Brittonic language. A case in point is the following remedy for “guædgou” [parasitic complexion]:

Cæs scau; cæs spern; cæs guærn; cæs dar; cæs cornucærui; cæs colænn; cæs aball per cæruisam. Anroæ æniap æhol pær mæl.

[Take elder / fox-glove; take thorn; take alder; take oak; take staghorn; take holly; take apple-tree with beer. Poultice all the face with honey.] (ed. and trans. Falileyev & Owen, 2005)

In this remedy, all words, except Latin per/pær ‘with’, cornucærui ‘staghorn’ and cæruissam ‘beer’, are in a Brittonic language, which may be either Cornish or Breton (see Falileyev & Owen, 2005).

The manuscript’s provenance, scripts and languages thus are indicative of the pluriform origin story of the Leiden Leechbook which must include references to Fleury, France, Ireland, as well as Cornwall or Britanny. But there is more to the Leiden Leechbook: there may be a connection to Anglo-Saxon England as well!

Is that an Old English gloss or should I put a child’s urine in my eyes?

According to the German scholar O. B. Schlutter (1910), the Leiden Leechbook also contains three words in Old English. The first word, he suggested, was accidentally copied into one of the Latin remedies for a headache. The Latin remedy suggesting you eat cooked crow’s brains to cure your own aching brain reads: “cornicis … exrebellum coctum” [cooked brains of a crow]. The word exrebellum does not exist in Latin and this should have read cerebellum ‘brains’. According to Schlutter, the scribe made a mistake when he copied a Latin exemplar that read ‘cerebellum’ with an Old English gloss ex – the scribe accidentally copied the gloss into the main text and forgot to write down “ce”, producing the nonce word exrebellum. Falileyev & Owen (2005, p. 28) reject this hypothesis by Schlutter, claiming “[i]t is difficult to see how an AS word meaning ‘axe’ should be used to gloss cerebellum“. It should be noted, however, that the Old English word ex was, in fact, used for ‘brains’ in various Old English medical texts and the Dictionary of Old English (s.v. ex 2, exe) confirms Schlutter’s suggestion.

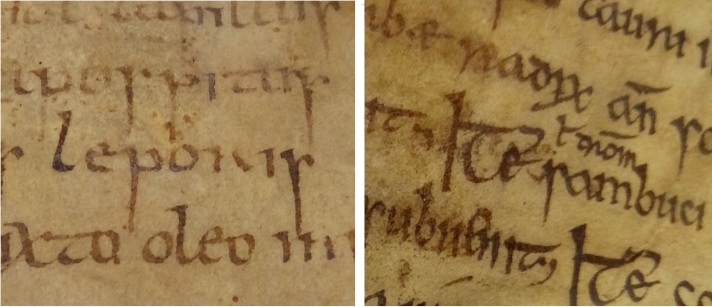

Schlutter identified another Old English word as an interlinear gloss in the following remedy for hairloss:

Ad capillos fluentes, leporis uentriculum coctum in sartagine et mixto oleo inpone capidi et capillos fluentes continet et cogit concrescere.

[For loose hair: put the stomach of a hare, cooked in a frying pan and mixed with oil, to the head, and that holds together loose hair and causes it to grow strong.] (ed. and trans. Falileyes & Owen, 2005)

According to Schlutter, an Old English gloss hara ‘hare’ had been added above the Latin leporis ‘of a hare’ – only the “h” is clearly visible, he writes, the rest has faded away. The most recent editors of the manuscript (Falileyev & Owen, 2005) reject Schlutter’s reading and claim that what Schlutter had seen is nothing other than a damage mark or scrape. You be the judge:

The third Old English word spotted by Schlutter is again rejected by Falileyev & Owen as an ink offset. This time, the Old English gloss is supposedly found in the headache remedy prescribing the crushed seeds of the elder tree. Here, Schlutter saw the Old English word ellærn ‘elder tree’ as a gloss for Latin sambuci (which was also glossed with Old Irish tromm). Despite Falileyev & Owen’s rejection, Schlutter’s reading is supported by the Dictionary of Old English (s.v. ellen noun 2, ellern) and, indeed, it is possible to make out some of the letters:

Are there three Old English words in the Leiden Leechbook, as Schlutter suggested, or none, as Falileyev & Owen argue?

There is one more reason to assume an Anglo-Saxon influence on the Leiden Leechbook: some of its remedies turn out to have (near) analogues in Old English medical texts. One such remedy is a cure for blurry eyesight, which is also found in the Old English Leechbook III:

Leiden Leechbook: Ad caliginem: lotium infantis si cum melle optima misces et iunges patientem.

[For clouded/blurred vision: if you mix the urine of a suckling child with honey of superior quality you will then heal the patient.] (ed. and trans. Falileyev & Owen, 2005)

Leechbook III: Gif mist sie fore eagum nim cildes hlond 7 huniges tear meng tosomne begea emfela smire mid þa eagan innan.

[If a mist be before the eyes, take a child’s urine and a drop of honey, mix together the same amount of both, rub the inside of the eyes with it.]

The existence of Old English analogues for some of the Leiden Leechbook’s remedies is an argument in favour of connecting the manuscript to Anglo-Saxon England. This connection, in turn, would strengthen the case for the existence of the Old English words spotted by Schlutter.

Are the Old English glosses hara and ellærn really in the Leiden Leechbook? I have looked long and hard at the manuscript and I cannot be sure whether the marks are letters, as Schlutter suggested, or damages to the parchment, as Falileyev & Owen argue; perhaps I should have another look after I have rinsed my eyes with child’s urine and honey…

If you liked this post, why not follow the blog (see button in the right-hand menu) and/or continue reading the following blogs on medieval medicine:

- Early Medieval Magical Medicine: An Anglo-Saxon Trivia Quiz

- Creepy Crawlies in Early Medieval England: Anglo-Saxon Medicine and Minibeasts

- How to cook your dragon and a medieval cure for old age

- Anglo-Saxon aphrodisiacs: How to arouse someone from the early Middle Ages?

Works referred to (and recommended reading on the Leiden Leechbook):

- Bremmer, Rolf H., Jr & Dekker, K., Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts in Microfiche Facsimile. Vol 13: Manuscripts in the Low Countries (Tempe, AZ, 2006)

- Falileyev, A. & Owen, M. E., The Leiden Leechbook: A Study of the Earliest Neo-Brittonic Medical Compilation (Innsbruck, 2005)

- Schlutter, O. B., ‘Anglo-Saxonica: Altenglisches aus Leidener Handschriften’, Anglia 33 (1910): 239-245.

Amazing post, thank you! And for the book recommendations, I’ve been trying to find an English translation and it just doesn’t seem to exist. I’m always looking for books to add to my AS medical library.

LikeLike

Could that “herb by the river” be a form of willow?Aren’t willows a source of the main ingredient of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid)? Fascinating blog post as always.

LikeLiked by 1 person