Language can be a window to culture: by studying Old English words, we can get an insight into how the Anglo-Saxons saw the world around them. This blog post considers Old English words for fingers, pigs, old age and anger. All word clouds were made with www.tagul.com. Information about Old English words is taken from the Thesaurus of Old English.

Old English words and Anglo-Saxon worldviews

In order to study the culture of the Anglo-Saxons, scholars first tend to turn to archaeology, history, literature and art. However, language can also be a valuable source for cultural analysis, as the famous linguist Edward Sapir has noted:

Vocabulary is a very sensitive index of the culture of a people and changes of the meaning, loss of old words, the creation and borrowing of new ones are all dependent on the history of culture itself. Languages differ widely in the nature of their vocabularies. Distinctions which seem inevitable to us may be utterly ignored in languages which reflect an entirely different type of culture, while these in turn insist on distinctions which are all but unintelligible to us. (Sapir 1951)

In other words, vocabulary reflects culture. Indeed, Old English words such as gafol-fisc ‘tribute fish’, cēapcniht ‘bought servant’, þri-milce-mōnaþ ‘May; lit. three-milk-month’, demonstrate that the Anglo-Saxons could pay tribute in fish, buy servants and milked their cows three times a day in May. Similarly, the etymology of Old English words for lord, lady, retainer and slave reveal traditional (perhaps pre-Anglo-Saxon) role patterns, in a household based on bread:

hlāford ‘lord’ (< *hlāf-weard ‘guardian of the bread’)

hlǣfdige ‘lady, woman’ (< *hlāf-dige ‘kneader of the bread’)

hlāfǣta ‘dependant, retainer’ (< *hlāf-ǣta ‘eater of the bread’)

hlāfbrytta ‘slave’ (< *hlāf-brytta ‘dispenser of the bread’)

In this blog post, I will take a cursory glance at four ‘semantic fields’ (fingers, anger, old age and pigs) in order to find out what some Old English words may tell us about Anglo-Saxon culture.

Philological finger food

The names we give to our fingers clearly reveal what we do with these fingers: on our ring-finger we wear our rings and with our index-finger we ‘indicate’ things (or: go through an index). Old English finger names are no different. Consider these words for the index-finger and ring-finger:

bīcn(ig)end ‘forefinger; lit. indicator’

scyte(l)finger ‘forefinger; lit. shot-finger’

tǣcnend ‘forefinger; lit. signer’

lēawfinger ‘forefinger; lit. betray-finger’

hringfinger ‘ring-finger’

goldfinger ‘ring-finger; lit. gold-finger’

lǣcefinger ‘ring-finger; lit. physician-finger’

These finger names yield few surprises: with their forefingers, the Anglo-Saxons pointed at things, shot arrows and made signs; they wore rings and gold on their ring-fingers. Two finger names warrant some explanation. The first element in lēawfinger, first of all, is related to the Old English word lǣwan ‘to betray’ – the forefinger is “the pointer out, the betrayer” (Merrit 1954, p. 175-with thanks to deorreader in the comments below). Secondly, the name lǣcefinger ‘physician finger’ for ring-finger may be somewhat confusing; according to some, there was a vein from this finger that went all the way to the heart and, so, this finger could have medicinal properties.

Apart from the obvious middelfinger, the Thesaurus of Old English lists two contradictory words for the middle finger: ǣwiscberend ‘offender’ and hālettend ‘greeter’ – talk about sending mixed signals! [The Dictionary of Old English, s.v. hālettend suggests that the sense ‘middle finger’ for hālettend is caused by a scribal error and that the word really means ‘forefinger’] The pinky was not only the last and smallest finger (se lȳtla finger; se lǣsta finger), it was also the Anglo-Saxon implement of choice when it came to cleaning out their ears: ēarclǣnsend ‘ear-cleaner’, ēarfinger ‘ear-finger’ and ēarscripel ‘ear-scraper’.

‘Talk to the hand’? If we look at the Old English words for fingers, it seems as if the hand is the one doing the talking, telling us what the Anglo-Saxons did with their fingers.

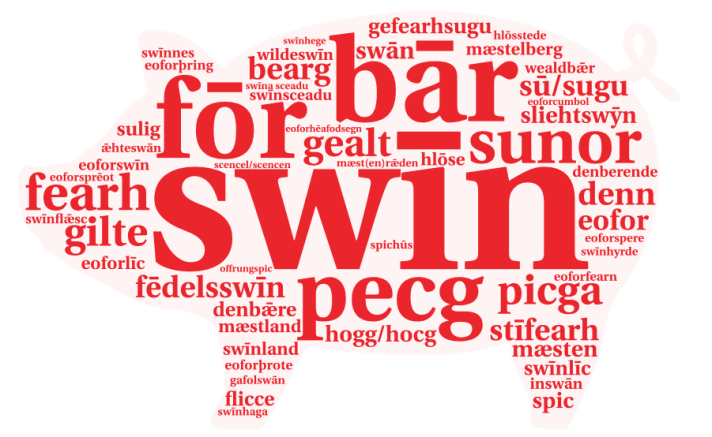

Of Pork and Pigs in Old English

With over sixty words related to ‘pig’, swine are among the best-represented animals in the Anglo-Saxon vocabulary. Indeed, an Anglo-Saxon could distinguish between fōr, pecg, swīn (all ‘pig’), sū/sugu (‘sow’), bār, gealt (both’ boar’), hogg/hocg (‘hogg’), fearh and picga (both ‘young pig’); next, he could pick from a host of ‘special pigs’, including gilte (‘barren sow’), bearg ‘castrated boar’, mæstelberg ‘fattened hog’ and fēdelsswīn (swine fattened for killing). There were no fewer than seven words for ‘swine pasture’ (denbǣre, denberende, denn, mæsten, mæstland, swīnland and wealdbǣr) and various words for swineherd (e.g., swān and swīnhyrde), pigsty (hlōse, sulig, swīnhaga) and even a word for pig-fence (swīnhege). Then there was the non-domesticated variety, the wild boar (bār, eofor, eoforswīn, wildeswīn) that had to be hunted with a boar-spear (eofor-spere, eofor-sprēot) and made an appearance on helmets and battle-standards (see: Boars of battle: The wild boar in the early Middle Ages). The Anglo-Saxons even saw boars when they looked up at the sky (their name for the constellation Orion is eofor-þring ‘boar-crowd’) or down at the plants near their feet (eofor-fearn ‘Polypody fern; lit. boar-fern’; eofor-þrote ‘Carline thistle; lit. boar-throat’).

Swine were appreciated, of course, for their meat, which is also well represented in the Old English lexicon: swīn, swīnflǣsc, swīnnes, flicce, spic, scencel/scencen. This meat would undoubtedly be stored in the pantry, which they called the spic-hūs: ‘the bacon-house’. Not all bacon would be in the bacon-house, however: some of it was offered to the gods. This much is at least suggested by the word offrung-spic ‘bacon offered to idols’ – there is no better tribute than sacrificial bacon!

Old in Old English

I wrote my PhD thesis on old age in Anglo-Saxon England (more info here) and one of the things I did was look at the fifty-two Old English words that denote old age in order to show what Anglo-Saxons associated with growing old. The word hār, for instance, means both ‘grey’ and ‘old’ – a clear connotation that is also found in a word like hārwenge ‘old; lit. grey-cheeked’. The word frōd means both ‘old’ and wise’, showing that the Anglo-Saxons associated old age with wisdom. The word geomor-frōd ‘grief-wise; old, sad and wise’ shows that wisdom came at a cost and was related to grief – gēomor-frōd is a lexical precursor of the modern English idiom ‘sadder and wiser’!

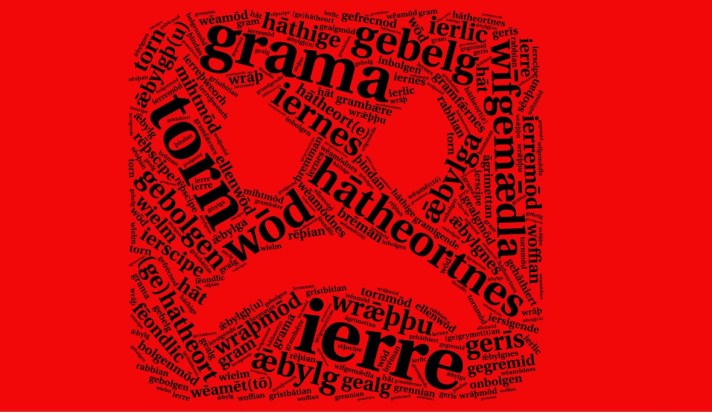

‘Angry words’ in Old English

The Old English vocabulary of anger is fairly well studied (see Gevaert 2002; Izdebska 2015) and scholars have been able to pinpoint, on the basis of these words and their usages, a number of ‘metaphorical links’. One such link is between ANGER and HEAT. Today, we can have a heated argument, we can be boiling with rage, until steam comes out of our ears. The Anglo-Saxons conceptualised ANGER in a similar way, as is revealed by such Old English words as hāt-heort-nes ‘anger; lit. hot-hearted-ness’ and hāt-hige ‘anger; lit. hot-mind’. At the same time, the Anglo-Saxons were aware that anger can be the result of despair or grief: the Old English word wēa-mōd-nes means ‘anger’ but can be analysed as ‘grief-minded-ness’ (cf. Dutch weemoed ‘grief’). Anger is also relatable to ‘swelling’. Just like we can be ‘puffed up with anger’, the Anglo-Saxons would speak of gebolgen, ǣbylga, belgan and gebelg (cf. Dutch verbolgen ‘angry’), which are all related to ābelgan ‘to swell up’. On the basis of these and other words, scholars have been able to demonstrate that Anglo-Saxons connected anger to PRIDE, WRONG EMOTION, UNKINDNESS, DARKNESS, HEAVINESS and so on (see Izdebska 2015; Gevaert 2002).

It is also interesting to note that the Anglo-Saxons had a specific word for the anger of a woman: wīf-gemædla ‘a woman’s fury’ – Apparently, Hell hath no fury like wīf-gemædla!

If you liked this post, you may also enjoy:

- Anglo-Saxon bynames: Old English nicknames from the Domesday Book

- What if Shakespeare HAD written Old English?

- Old English is alive! Five TV series and movies that use Old English

Works refered to:

- Gevaert, C. (2002). ‘The Evolution of the Lexical and Conceptual Field of ANGER in Old and Middle English’, in A Changing World of Words: Studies in English Historical Lexicography, Lexicology and Semantics, ed. J. E. Díaz Vera (Amsterdam), 275–300.

- Izdebska, D. W. (2015). Semantic field of ANGER in Old English. PhD thesis, University of Glasgow

- Meritt, H. D. (1954). Fact and Lore About Old English Words (Stanford)

- Sapir, E. (1951). ‘Language’, in Selected Writings of Edward Sapir in Language, Culture and Personality, ed. David G. Mandelbaum (Berkeley, 1951), 7–32.

I hadn’t realised that Anglo-Saxon was such a rich language. Thank you for showing me that it was.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure where you get “lēawfinger ‘forefinger; lit. learn-finger’” from. I know Bosworth-Toller suggests some OHG cognate ‘ge-lou’ which they say means means clever. But ‘leaw-‘ is probably from ‘lǣwan’, betray, which is much more interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re absolutely right; thanks for pointing (hah!) that out; I will edit accordingly.

LikeLike

Fixed!

LikeLike

Boom boom!

LikeLike

Thank heaven for sites like this. Thank heaven for those who run them. Please keep up the good work. I’m not sure you’ll have any successors. No less an authority than Oxford University itself is leading the latest assault on our people and its past, or so I’m told, with plans to drop (if it hasn’t dropped all ready) the Anglo Saxon component from its English curriculum. Shameful.

LikeLike