Manuscripts are among the most fascinating artefacts from the Middle Ages. This post focuses on a manuscript that was kidnapped by Vikings: The Stockholm Codex Aureus.

‘The Golden Book’

The Stockholm Codex Aureus (Stockholm, National Library of Sweden, MS A. 135) is an eighth-century Gospel book. This beautiful manuscript was probably made in Canterbury and would also have had a bejewelled bookbinding. The presence of a precious binding can be inferred from a note on the opening page that commemorates Wulfhelm, the goldsmith, Ceolheard, the jeweller, and someone named Ealhhun. These could be the monks who were involved in the making of the book or they may have been responsible for rebinding it at a later point in time (see Gameson 2001):

Orate p<ro> Ceolheard p<res>b<itero>, inclas [for inclusor?] 7 Ealhhun 7 Wulfhelm, aurifex

[Pray for priest Ceolheard, the jeweller(?), and Ealhhun and Wulfhelm, the goldsmith]

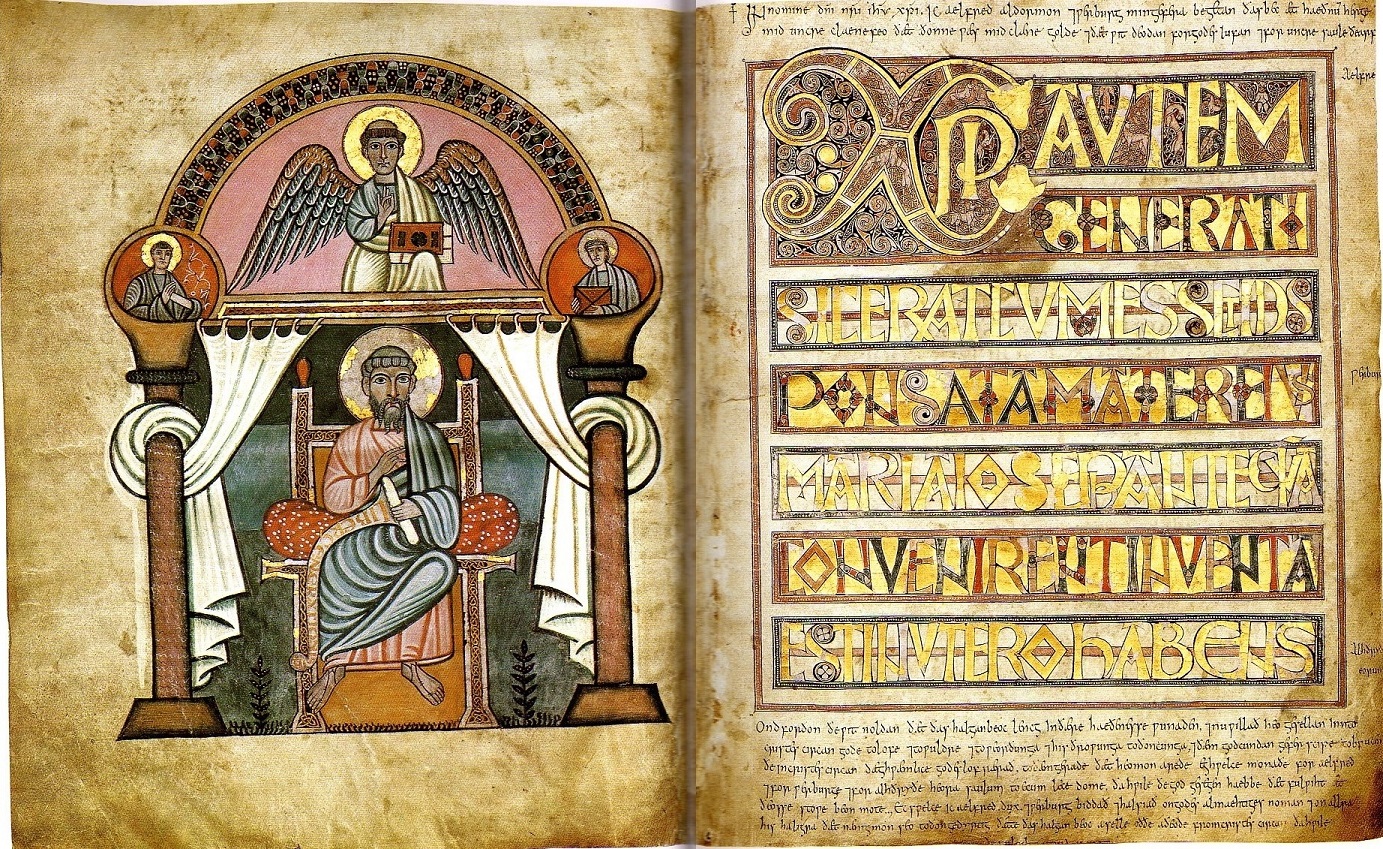

The Stockholm Codex Aureus (or: Canterbury Codex Aureus) owes its nickname ‘Golden Codex’ to the lavish use of gold-leaf for some of its initials. Its golden glory is best illustrated by the opening page of the Gospel of Matthew:

Kidnapped by Vikings!

The opening page of the Gospel of Matthew has more to offer than just its gold and decorated letters: a ninth-century note added in the upper and lower margin of the page relates the exciting history of this book. As it turns out, the Codex Aureus had once been stolen by Vikings and, as the note states, an Anglo-Saxon ealdorman and his wife had ransomed it from the heathen army:

In nomine Domini nostri Ihesu Christi Ic Aelfred aldormon ond Werburg min gefera begetan ðas bec æt haeðnum herge mid uncre claene feo, ðæt ðonne wæs mid clæne golde, ond ðæt wit deodan for Godes lufan ond for uncre saule ðearfe.

Ond for ðon ðe wit noldan ðæt ðas halgan beoc lencg in ðære haeðenesse wunaden, ond nu willað heo gesellan inn to Cristes circan Gode to lofe ond to wuldre ond to weorðunga, ond his ðrowunga to ðoncunga, ond ðæm godcundan geferscipe to brucenne ðe in Cristes circan dæghwæmlice Godes lof rærað, to ðæm gerade ðæt heo mon arede eghwelce monaðe for Aelfred ond for Werburge ond for Alhðryðe, heora saulum to ecum lecedome, ða hwile ðe God gesegen haebbe ðæt fulwiht æt ðeosse stowe beon mote.

Ec swelce ic Aelfred dux ond Werburg biddað ond halsiað on Godes almaehtiges noman ond on allra his haligra ðæt nænig mon seo to ðon gedyrstig ðætte ðas halgan beoc aselle oððe aðeode from Cristes circan ða hwile ðe fulwiht <stondan><mote>.

In the name of Our Lord Jesus Christ. I, ealdorman Alfred, and Werburg, my wife, obtained these books from the heathen arme with our pure money, that was with pure gold, and we did that for God’s love and for the sake of our souls.

And because we did not wish that these holy books would remain long among the heathens, and now we want to give it to Christ’s church for God’s praise, honour and glory, and in gratitude of his passion and for the use of the religious community, who daily raises up God’s praise in Christ’s church, on the condition that they are read every month for Alfred and for Werburg and for Alhthryth, for the eternal salvation of their souls, for as long as God should grant that the faith is allowed to be in this place.

Also likewise, I, ealdorman Alfred, and Werburg pray and ask in the God’s almighty name and those of all his saints that no man will be so bold as to deliver or separate these books from Christ’s church for as long as the faith is allowed to stand.

Having ransomed the book from the Viking army, Alfred and Werburg donated the book to the monastic community at Christ Church, Canterbury. In return, they expected the monks to pray for their souls and the soul of Alhthryth, who may have been their daughter. To make sure the monks would not forget them, the donators also had their names written in the right-hand margin of the same page: Alfred, Werburg, Alhthryth.

The beauty of the Chi-Rho page: Animals galore

The first page of the Gospel of Matthew in medieval Gospel books was often highly decorated. The so-called Chi-Rho page (named after the two first capital letters of Christ’s name) of the Stockholm Codex Aureus is no exception. What is striking about the first line of this page is its inclusion of no fewer than twenty animals. While some (like the lamb of God above the PI of ‘XPI’-abbreviation for Christ) are easy to find, other are hidden among the many decorations. I personally like how even the initial capital X terminates in two animal heads (cows?) and how one animal is trying to balance himself between the two arches of the M. The image below lists the twenty animals and their location in the words “XPI AUTEM”:

Bipolar pages

Another interesting feature of the Stockholm Codex Aureus is its consistent alternation of normal parchment pages with pages that were dyed purple. Whereas the white pages are written with black ink, the purple pages have lettering in gold and silver. The use of purple pages and gold ink is well attested for the seventh and eighth centuries: since gold and silver were durable metals, they were deemed the proper colours for the equally incorruptible word of God. Ironically, it was probably this use of gold in the Stockholm Codex Aureus (and its bejewelled cover) that made it catch the attention of the marauding Vikings in the ninth century.

While the Codex Aureus was temporarily returned to England, it did eventually end up in Scandinavia. The manuscript had remained in Canterbury until the end of the Middle Ages, then spent some time in Spain, but was finally acquired by the Royal Library of Sweden in 1690. I wonder how much “pure gold” it would take to ransom the book once more from these Vikings!

If you liked this blog post, you can sign up for regular updates and/or read the following posts about medieval manuscripts:

- An Anglo-Saxon comic book collector: Cuthwine and the Carmen Paschale

- Paws, Pee and Pests: Cats among Medieval Manuscripts

- The Illustrated Old English Hexateuch: An early medieval picture book

- Teaching the Passion to the Anglo-Saxons: An early medieval comic strip in the St Augustine Gospels

Works referred to:

- Gameson, R. (ed.), The Codex Aureus: An Eighth-Century Gospel Book (Copenhagen, 2001)

That’s a stunningly gorgeous book. I don’t know how the Saxons got their reputation for being poor artists.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course, the real story is how they managed to go amongst the Heathen Army and return unscathed. Having a large purse of gold on their persons would have made a tempting target for any Heathen–be they Dane or Saxon. Perhaps the Vikings admired their courage–or craziness–for coming into their midst unarmed simply to get a book back. I’m sure the tale would have been fascinating–pity we shall never know the details.

LikeLike

The provenance is C17, it only arrived in Sweden in 1690 after being ‘acquired’ by Johann Gabriel Sparwenfeld. The rest is flim-flam. Sorry but those are the rules of evidence that historians are supposed to follow.

“Provenance: In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it was in Spain, and in 1690 it was bought for the Swedish royal collection. It is now kept in the National Library of Sweden.

Ownership: Jerónimo Zurita (d. 1580); Carthusians of Aula Dei, Zaragoza; Count-Duke of Olivares, Gaspar de Guzmán (1587–1645). Acquired by J. G. Sparwenfeld 8. 1. 1690.”

LikeLike