From the Viking mead drinking in Valhalla to the unending punishments of the Greek underworld, the afterlife has always been an imaginative place. In this blog post, I survey how the afterlife was conceptualised in early medieval England, in particular with reference to ‘old age’.

Heaven is a place without old age

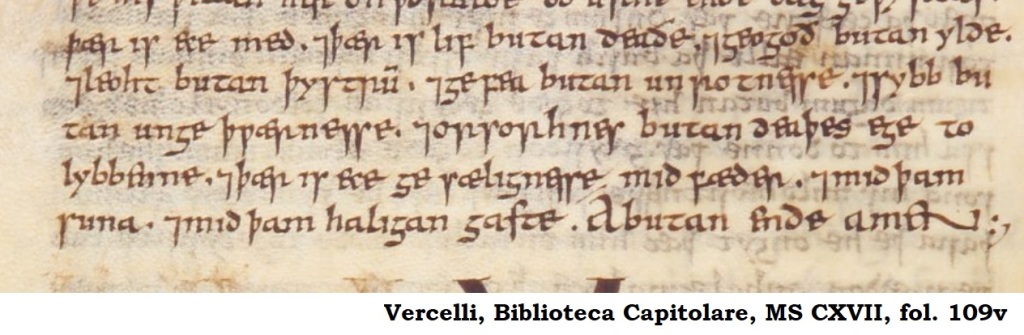

The prime place to look for descriptions of Heaven are Old English homilies. As I have pointed out in another blog post (“Men þa leofestan!” Manuscript variations of an Old English formula), these homilies are highly formulaic and, indeed, various descriptions of Paradise look very much alike. In fact, similar descriptions of ‘The Seven Joys of Heaven’ are found in no fewer than eleven Old English homilies. They are easy to spot, since they use the recurring formula ‘þær is x butan y’, where both x and y are antonyms, to describe what is present and what is absent from Paradise. A typical example is found in one of the homilies of the Vercelli Book:

Þær is ece med, 7 þær is lif butan deaðe 7 geogoð butan ylde 7 leoht butan þystrum 7 gefea butan unrotnesse 7 sybb butan ungeþwærnesse 7 orsorhnes butan deaþes ege to lybbenne, 7 þær is ece gesælignesse mid fæder 7 mid þam suna 7 mid þam haligan gaste a butan ende, amen.

[There is the eternal reward and there is life without death and youth without old age and light without darkness and joy without sadness and peace without violence and carelesness without living in fear of death, and there is the eternal happiness with the Father and with the Son and with the Holy Ghost, always, without end, Amen.]

(Vercelli Homily XIX)

A more poetic version of this topos is found in the Old English poem Christ III, which describes Heaven as follows:

Đær is leofra lufu,____ lif butan endedeaðe,

glæd gumena weorud,____gioguð butan ylde,

heofonduguða þrym,____hælu butan sare,

ryhtfremmendum ræst ____butan gewinne,

domeadigra____ dæg butan þeostrum,

beorht blædes full,____blis butan sorgum,

frið freondum bitweon____forð butan æfestum,

gesælgum on swegle, ____sib butan niþe

halgum on gemonge.[There is the love of beloved ones, life without death, a joyous troop of men, youth without old age, glory of heavenly hosts, health without pain, rest without toil for the well-doers, day without darkness for the renowned ones, bright full of glory, bliss without sorrows, peace between friends without envy, happy in harmony, peace without envy, among the saints]

(Christ III, ll. 1652-1660)

In these iterations of Heaven, old age is again and again notably absent. Apparently, spending eternity in an aged body was regarded as the antithesis of a joyful afterlife. Indeed, similar descriptions of Hell include old age among its horrors.

The road to Hell is paved with grey hairs

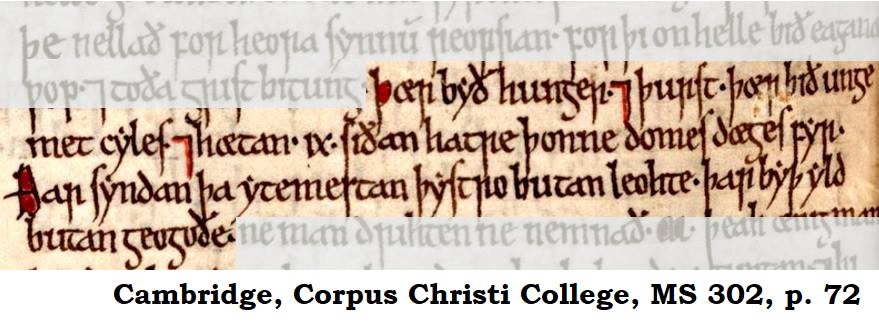

The description of Hell in the Old English homily “Be heofonwarum 7 be helwarum” [about the Heaven-dwellers and the Hell-dwellers] is almost a complete reversal of the stock description of Heaven:

Þær byð hunger 7 þurst. Þær bið ungemet cyles, and hætan IX siðan hatre þonne domesdæges fyr. Ðar syndan þa ytemestan þystro butan leohte, þar byð yld butan geoguðe.

[There is hunger and thirst. There is unmeasurable cold and heat nine times hotter than the fire of Doomsday, there is the utmost darkness without light, there is old age without youth.]

(“Be heofonwarum 7 be helwarum”)

Here, old age is clearly presented as one of the ‘horrors of Hell’, one that does not even need a qualifier like ‘unmeasurable’, ‘utmost’ or ‘nine times hotter than the fire of Doomsday’.

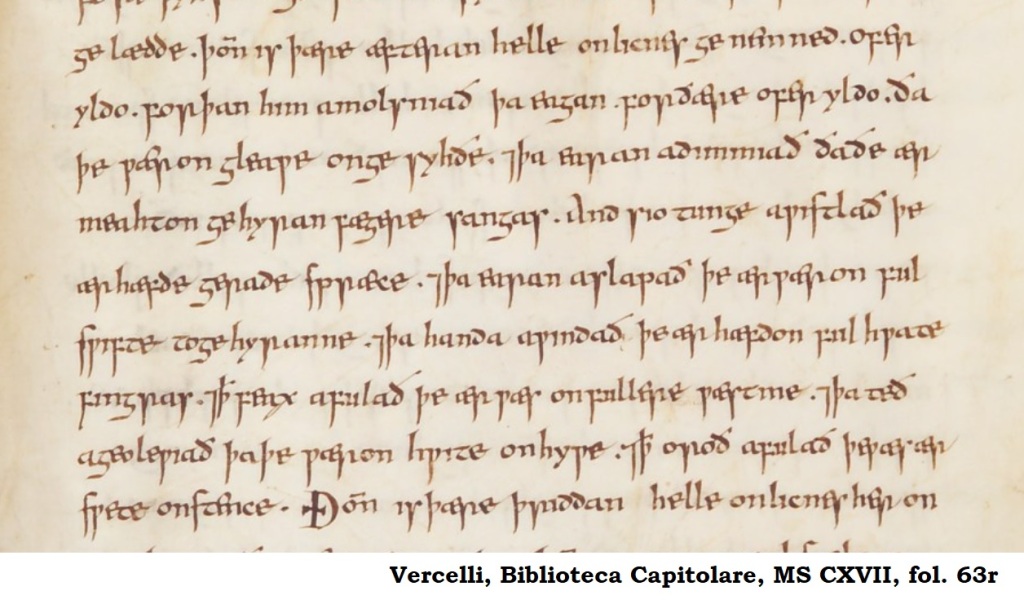

Rather more expressively, another Old English homilist lists ‘old age’ as one of the five ‘prefigurations of Hell’, along with pain, torture, death and the grave:

Þonne is þære æfteran helle onlicnes genemned oferyldo, for þan him amolsniaþ þa eagan for þære oferyldo þa þe wæron gleawe on gesyhþe, 7 þa earan adimmiaþ þa þe ær meahton gehyran fægere sangas, and sio tunge awlispaþ þe ær hæfde gerade spræce, 7 þa fet aslapaþ þe ær wæron ful swifte 7 hræde to gange, 7 þa handa aþindaþ þe ær hæfdon ful hwate fingras, 7 þæt feax afealleþ þe ær wæs on fullere wæstme, 7 þa teþ ageolewiaþ þa þe ær wæron hwite on hywe, 7 þæt oroþ afulaþ þe wæs ær swete on stence.

[Then is the second prefiguration of Hell named ‘old age’, because for him the eyes weaken because of old age, those that had been keen of sight, and the ears become dim, those that had been able to hear beautiful songs, and the tongue stammers, that had had skilful speech, and the feet sleep, those that had been very swift and quick in movement, and the hands become swollen, that had had fully active fingers, and the hair falls out, that had been full of abundance, and the teeth become yellow, those that had been white in appearance, and that breath, which had been sweet of smell, becomes foul.]

(Vercelli Homily IX)

Want to know what Hell is like? Grow old!

The magical number is 33

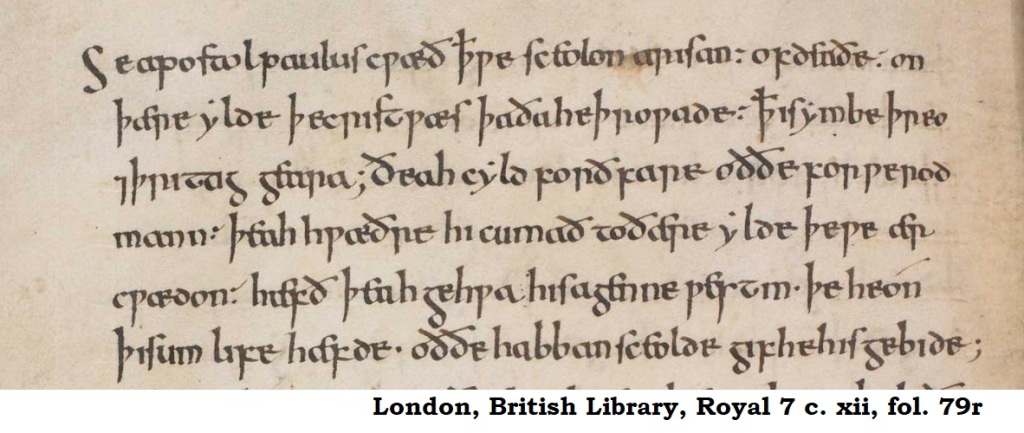

So if one was not old in Heaven, how ‘young’ would one be? The answer is 33. The homilist Ælfric of Eynsham noted that, according to the Apostle Paul, everyone would be resurrected on Doomsday at the same age at which Christ was crucified:

Se apostol paulus cwæð þæt we sceolon arisan of deaðe on þære ylde þe crist wæs þa ða he þrowade þæt is ymbe þreo and þrittig geara. Đeah cyld forðfare oððe forwerod mann þeahhwæðre hi cumað to ðære ylde þe we ær cwædon hæfð þeah gehwa his agenne westm þe he on þisum life hæfde.oððe habban sceolde gif he his gebide.

[The Apostle Paul said that we shall arise from death at the age that Christ was when he suffered, that is around thirty-three years. Eventhough a child or a worn-out old man departs, nevertheless they will arise at the age we said before; nevertheless everyone will have his own growth which he had in this life or should have had if he had experienced it.]

(Ælfric of Eynsham, Catholic Homilies I, 16)

Coincidentally, a 20212 study showed that the age of 33 is still the age at which people are at their happiest (source). Judging by the descriptions of Heaven and Hell above, however, this restoration of human bodies to their prime on Doomsday only lasted for those who would go to Heaven; for the souls assigned to the Abyss, their regained physical prime would turn out to be short-lived – they would spend the rest of eternity in the withered, hairless, yellow-teethed and foul-breathed body of an old person.

Want to know more about old age in early medieval England? You are in luck: Boydell and Brewer are offering a 40% discount on my book Old Age in Early Medieval England: A Cultural History (2019) – see the code in the Tweet below (valid until 31 December, 2020!):

You can also sign up below for regular blog updates!