Gashed gatherings, bodged bindings and faltering flyleaves. The current state of medieval manuscripts, either good or bad, reflects the manner in which manuscripts have been retained and used over the centuries. Nowadays, the concern over the preservation of books leads to ever stricter regulations on access, handling and storage. But what about the Middle Ages? Did contemporary makers or users of books set any rules on how to treat these objects? This blog post calls attention to a late medieval Middle Dutch text which provides guidelines as to how to preserve books ‘to last forever’ -some of these rules remain topical today!

Caring for books in the Middle Ages

Medieval, written sources on the care of books are relatively scarce. An interesting case is the Philobiblon, written by Richard de Bury (1287-1345). In this work of passionate bibliophilia, Richard expresses his profound love for books. He also shows an awareness of the dangers that threaten a book’s well-being. Not least of all, Richard laments the maltreatment of manuscripts by snotty youths, who, rather than wipe their noses, stain their books:

You may happen to see some headstrong youth lazily lounging over his studies, and when the winter’s frost is sharp, his nose running from the nipping cold drips down, nor does he think of wiping it with his pocket-handkerchief until he has bedewed the book before him with the ugly moisture. Would that he had before him no book, but a cobbler’s apron! (De Bury, ch. 17)

In monastic libraries, some measures were taken to prevent damage to books. Most monasteries appointed a so-called armarius, a librarian avant la lettre, who was responsible for managing and preservation of the manuscripts (Clark 1902: 57). According to the fifteenth-century monastic rules of the St. Paul’s house for the Brethren of the Common Life in Gouda, the armarius was also supposed to take into account the dangers posed by bookworms and dust (Lem 1991). Other monasteries add dirt, and damage caused by humidity and/or fire to these instructions (Clark 1902: 61). None of these monastic rules provide any practical advice, however, as to how these risks could be minimised.

‘How one shall preserve all books to last eternally’

Specific rules and practical advice on book conservation is provided by the author of the text entitled ‘Hoemen alle boucken bewaren sal om eewelic te duerene’ [How one shall preserve all books to last eternally]. This unique text, in the Dutch vernacular, outlines eight rules on access, handling and storage. The text is found in The Hague, KB 133 F 2: a miscellany on 180 folia of 120x79cm, written entirely by one hand. Various ownership inscriptions, in the hand of the main text, suggest this book was made in 1527 and that it belonged to ‘Margrieten van der Spurt’ from Ghent, in present-day Belgium. The contents of this manuscript suggest that this book was used as an educational treatise for children. Most texts have a didactic nature, such as a text entitled “eenen gheestelicken A.B.C.” [a spiritual A.B.C.], while others focus on the ways in which children should treat their parents, bearing running headers such as “in quade kinderen sal niement verblijden” [evil children will not make anyone happy] and “vader ende moeder moet men in alder noot bijstaen” [one must help one’s father and mother in every need].

The text ‘hoemen boucken bewaren sal om eewelic te duerene’ immediately follows the first ownership inscription and is the first stand-alone text of the manuscript. The prominent place of this text within the manuscript may attest to the educational import of conveying rules of book preservation to a child of the first half of the sixteenth century.

So what does the text actually tell us to do? In the introduction, the author remarks that, if the reader followed his guidelines, books would last “menich jaer[…], ja te minsten twee hondert jaer” [many years…, yes, at least two hundred years]. In short, his eight rules run as follows:

- Store your books in a dry and dustless place.

- Do not handle your books with dirty fingers.

- Do not let your books lie near the fire or leave them open for too long.

- Never pull the pastedowns off the boards.

- Preserve books from mold and decay, by, for example, not drying it in the winter or touching it with wet fingers.

- Do not tear out a page or quire.

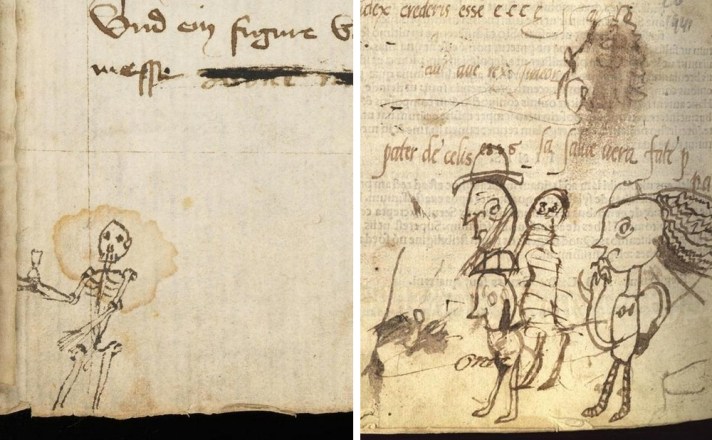

- Do not doodle or add texts in the margins.

- Do not give your books to children.

For each of these rules, the author outlines what would happen if the reader did not follow the rule. For the third rule, for example, the author notes: “want aldus soude den rugghe metten banden crempen ende naermaels ter stont breken” [because this would make the spine shrink with the cords and would make it break immediately].

Do not give your books to children!

Interestingly, the eighth rule (in violation of the seventh rule) was added in the margin only after the text was finished: “Ten 8sten, men sal huut gheenen boucken diemen ter heeren hauwen wilt, de kinderen laten leeren. Want wat in haerlieder handen comt, soe wij sien het blijfter oft het bedeerft.” [Eighth, one should not let children learn from any books that one wants to preserve. Because whatever comes into their hands, as we see, it either stays there or it is ruined]. The rule was added by the same scribe who wrote down the first seven rules. Given that this manuscript was probably used as an educational treatise for children, the addition of the eighth rule may have been due to ‘progressive insight’ on account of the author.

Nevertheless, the fact that, with the exception of the original binding, the book that contains these eight rules is still available in the Royal Library in The Hague in the twenty-first century, proves that the manuscript has far exceeded its expected 200-year life span. We can only conclude, then, that the contemporary and later users of this manuscript abided by the rules outlined above and that they took to heart the moral which was added at the end of the text:

“Men pleegt te segghene an de plume sietmen wat vueghel dat es ende an eens cleercs boucken sietmen wel wat cleerc dat es. Ende alsoe weetmen gheware an de boucken van de lieden of se reijn van ijet te beseghen, goddelic ofte duechdelic van levene sijn.”

[They say that one can recognise a bird by its plumage, and one can recognise a clerk by his books. And so it will be revealed by the books of people, whether they are clean, god-fearing or good of living.]

For those interested in the text ‘Hoemen alle boucken bewaren sal om eewelic te duerene’, an edition and introduction have been published (in Dutch) as: T. Porck & H.J. Porck,‘Hoemen alle boucken bewaren sal om eewelic te duerene. Acht regels uit 1527 over het conserveren van boeken’in: Jaarboek voor Nederlandse Boekgeschiedenis 15 (2008), 7-21. A thoroughly revised, English version of the article, featuring an English translation of the text, is published as: T. Porck & H.J. Porck, ‘Eight Guidelines on Book Preservation from 1527: How One Should Preserve All Books to Last Eternally’, in: Journal of PaperConservation 13(2) (2012), 17-25. An Open Access version of the English article is available here.

Works referred to:

- Clark, John (1902). The Care of Books. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- De Bury, Richard. Philobiblon. Ed. and trans. by E.C. Thomas (1888).

- Lem, Constant, (1991). ‘De Consuetudines van het Collatiehuis in Gouda.’ Ons Geestelijk Erf 65, 125-143.

This is an edited version of a blog previously posted on the medievalfragments blog.

3 thoughts on ““Do not give your books to children!” and other medieval tips for taking care of books”