In this blog, I have occasionally noted how illustrated manuscripts resemble the comic books and graphic novels of this day and age (see here and here). In this post, I focus on the eighth-century Cuthwine, bishop of Dunwich, who appears to have had a taste for illustrated manuscripts: an Anglo-Saxon comic book collector!

Bishop Cuthwine of Dunwich and his illuminated manuscripts

Cuthwine was bishop of Dunwich somewhere between 716 and 731. Little is known about Cuthwine, apart from his interest in illuminated manuscripts. This interest is revealed by the Anglo-Saxon monk and scholar Bede (d. 735) in a work entitled The Eight Questions; Bede suggests that he had seen an illuminated manuscript that Cuthwine had brought back from Rome. Bede brings up Cuthwine’s manuscript in reply to a question by the London priest Nothelm about what the Apostle Paul meant when he said “Five times I have received from the Jews the forty minus one” (2. Cor. 11:24):

What the Apostle says … signifies that he had been whipped by them five times, in such a way, however, that he was never beaten with forty lashes, but always with one less, or thirty-nine. … That it is to be understood in this way and was understood in this way by the ancients is also attested by the picture of the Apostle in the book which the most reverend and most learned Cuthwine, bishop of the East Angles, brought with him when he came from Rome to Britain, for that book all of his sufferings and labours were fully depicted in relation to the appropriate passages. (trans. Trent Foley & Holder 1999, p.151)

The book described by Bede has been identified as the De actibus apostolorum, a verse history of the Apostles by the sixth-century poet Arator. While this particular copy of Cuthwine’s has not survived, the name of this Anglo-Saxon bishop has been connected to another manuscript.

Cuthwine’s copy of the Carmen Paschale by Sedulius

Antwerp, Plantin-Moretus Museum, M 17.4 contains an illustrated versification of the life of Christ, known as the Carmen Paschale by the early fifth-century Roman poet Sedulius. According to art historian Alexander (1978, p. 83), the Antwerp manuscript represents a ninth-century Carolingian copy of an earlier Anglo-Saxon exemplar. It is possible that this Anglo-Saxon exemplar once belonged to Cuthwine, since the copiist of the Antwerp manuscript copied a colophon of another text in the manuscript, which mentions the name “CUĐUUINI”:

The fact that the Antwerp manuscript is based on an Anglo-Saxon exemplar coupled with Bede’s report on Cuthwine’s interest in illuminated manuscripts has led scholars to suggest that the exemplar of this manuscript once belonged to this Anglo-Saxon bishop (e.g. Lapidge 2006, pp. 26-27).

As I will reveal at the end of the blog post, the Antwerp manuscript may have something peculiar in common with the manuscript described by Bede as having belonged to Cuthwine, aside from just being illustrated. But let’s look at some of the illustrations of the Carmen Paschale first.

The Carmen Paschale: The Bible as an epic poem

Sedulius’s Carmen Paschale attempts to rewrite the Gospels in the style of classical epics, such as Vergil’s Eneid. Apart from the story of Christ, the poem also contains various references to Old Testament stories. To give you an idea of the nature of the poem, here is the text that accompanies an image of Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac in the Antwerp manuscript:

The enfeebled uterus of old Sarah was already withering,

Worn out by long inactivity, and the chilly blood,

Moribund in her ancient body, was denying her a child.

Her husband was even older than she, when the insides of her cold belly

Began to swell to give new birth, and the trembling mother,

Grown heavy in her freezing womb, produced hope for a fertile race

And held a late-born son up to her breasts.

His father brought him to God to sacrifice, but instead, a sacred ram

Was slaughtered, and the boy’s throat was spared right at the altar. (bk. I, ll. 107-115, trans. Springer 2013)

Sedulius’s style has been described as bombastic, and rightly so, judging by his description of Sarah’s withered uterus!

Jonah and the whale

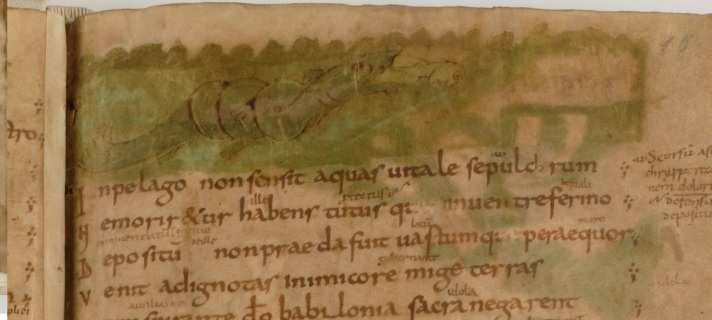

The illustrations in the Antwerp manuscript generally illustrate the text of the poem well, as the two illustrations of the story of Jonah and the whale illustrate:

Jonah fell off a ship and was swallowed up by a voracious whale.

Even in the sea he did not get wet, for he was in a living tomb,

So that he would not perish. Safe in the wild beast’s belly,

He was its charge, not its prey, and over the great expanse of the sea,

Rowed by an unfriendly oarsman, he arrived in unfamiliar lands. (bk. I, ll. 192-196, trans. Springer 2013)

Whipped saints and martyred babies: Cuthwine’s taste for gore

If the illustrations in the Antwerp manuscript resemble those of the Anglo-Saxon exemplar (and Alexander 1978 seems to think so), we might attribute to Cuthwine a certain taste for blood and gore. Both the Antwerp manuscript and Cuthwine’s manuscript described by Bede contained illustrations with a lot of graphic detail. Bede describes the scene of St. Paul’s flogging in Cuthwine’s manuscript as follows:

This passage was there depicted in such a way that it was as if the Apostle were lying naked, lacerated by whips and drenched with tears. Now above him there was standing a torturer having in his hand a whip divided into four parts, but one of the strings is retained in his hand, and only the remaining three are left loose for beating. Wherein the intention of the painter is easily apparent, that the reason he was prepared to scourge him with three strings was so that he might complete the number of thirty-nine lashes.(trans. Trent Foley & Holder, p. 151)

Apparently, the artist of Cuthwine’s book had not left much to the imagination. Much the same can be said for the image in the Antwerp manuscript, depicting the martyrdom of the Holy Innocents (the young male children in the vicinity of Bethlehem, massacred by Herod):

Indeed, the image of warriors cutting babies in half, a baby impaled on a spear and the attempts of their mothers to embrace the dead babies is gruesome by any account and well accompanies Sedulius’s outrage over the massacre:

And he kept on dashing to the ground and slaying masses of infants,

Fierce in his unwarranted murder. For what crime did this innocent

Multitude have to perish? Why did those who had barely begun to live

Already deserve to die? There was rage in the bloodthirsty king,

Not reason. Killing them at their first cries and daring to

Perpetrate wickednesses beyond number, he slaughtered boys

By the thousands and gave a single lament to many mothers.

This one tore out her mangled hair from her bare scalp.

That one scored her cheeks. Another beat her bared breast with fists.

One unhappy mother (now a mother no longer!)

Bereft, pressed her breasts to her son’s cold mouth-in vain.

You butcher! What did you feel then as you watched such a sight? (bk. II, ll. 116-127, trans. Springer 2013)

When one compares Sedulius’s text to the illustration, it is interesting to note that much of the brutality in the Antwerp manuscript illustration was added by the artist. Sedulius focuses on the reaction of the mothers and nowhere mentions babies being cut in half or impaled on spears. Speculatively, we might imagine the artist of the original, Anglo-Saxon exemplar of the Antwerp manuscript adding these gory details, since he knew Bishop Cuthwine’s taste for such scenes. I wonder what Cuthwine felt when he “watched such a sight”….

If you liked this post, you may also enjoy other posts about illuminated manuscripts:

- Teaching the Passion to the Anglo-Saxons: An early medieval comic strip in the St Augustine Gospels

- The Illustrated Old English Hexateuch: An early medieval picture book

Works referred to:

- J.J.G. Alexander, Insular Manuscripts: 6th to the 9th Century (London, 1978)

- Bede, A Biblical Miscellany, trans. W. Trent Foley & A. G. Holder (Liverpool, 1999)

- Lapidge, M. The Anglo-Saxon Library (Oxford, 2006)

- Sedulius, The Paschal Song and Hymns, trans. C. P. E. Springer (Atlanta, 2013)

I love getting your blogs, they are so interesting and have told me things I never knew. At 75 I thought I knew it all, well most of it anyway. Thank you

LikeLike

That’s great to hear; thanks!

LikeLike

This is really fascinating. Thanks, Thijs.

LikeLike