As a professor of Anglo-Saxon at the University of Oxford, J. R. R. Tolkien could not help but be inspired by the language and literature he studied and taught. As a result, his fictional world is infused with cultural material of the Middle Ages, particularly Old English language and literature. In this post, I focus on the hobbits and their early medieval antecedents.

At first glance, there appears to be no resemblance of any kind between Tolkien’s peacable hobbits and the warlike early medieval Anglo-Saxons that conquered parts of Britain in the early Middle Ages; yet, there is more to these hobbits than meets the eye…

Old English roots: Holbytlan, scir, þegn, miclan delfing…

‘Are not these the Halflings, that some among us call the Holbytlan?’, Théoden asks, when he first sets eyes on Pippin and Merry on the outskirts of Isengard. Théoden’s word holbytla ‘hole-dweller’ is Tolkien’s own invented Old English etymology for the word Hobbit and means ‘hole-dweller’. Other Hobbitish terms have more clear Old English roots: the Shire itself stems from the Old English word scir ‘district’ as does the name of its principal administrator: the Thain, from Old English þegn ‘servant’. Hobbitish place names, too, derive from the language of the Anglo-Saxons: Michel Delving, for instance, is clearly Old English miclan delfing ‘great excavation’. Old Hobbitish, it seems, is nothing other than Old English!

What’s in a name? Hengist, Horsa, Marcho and Blanco

The story of how Hobbits came to settle in the Shire, as outline in the prologue to The Fellowship of the Ring, bears a keen resemblance to the foundation myth of the Anglo-Saxons. About the first Shire-Hobbits, Tolkien notes that the “Fallohide brothers, Marcho and Blanco” first crossed the river Baranduin, with a great following of Hobbits – the year of the crossing was to become the first year of Shire-reckoning. The names Marcho and Blanco both mean ‘horse’ and, thus, resemble the names of the two brothers who supposedly had led the Germanic tribes to Britain: Hengest and Horsa, whose names mean ‘stallion’ and ‘horse’.

Of mathoms and silver spoons

The hobbits’ fondness for mathoms also aligns them with the Anglo-Saxons:

The Mathom-house it was called; anything that Hobbits had no immediate use for, but were unwilling to throw away, they called a mathom. Their dwellings were apt to become rather crowded with mathoms, and many of the presents that passed from hand to hand were of that sort. (The Fellowship of the Ring, prologue)

The word mathom is derived from the Old English maðm ‘treasure’. The word appears in such poems as Beowulf, where it describes the gifts bestowed upon warriors by kings:

‘Me þone wælræs wine Scildunga

fættan golde fela leanode,

manegum maðmum‘ (Beowulf, ll. 2101-2103a)[The friend of the Scildings gave me a lot of plated gold, many treasures, in exchange for the battle]

From Beowulf, we learn that mathoms could include decorated and bejewelled swords and armour, such as those found at Sutton Hoo (on display at the British Museum, here). Hobbitish mathoms turn out to be of a similar sort: the Mathom-house in Michel Devling is filled with weapons of such long-forgotten battles as the Battle of the Greenfields, “in which Bandobras Took routed an invasion of Orcs.” Bilbo’s presents at his eleventy-first birthday may be mathoms of a different kind, but at least one of them can also be linked to the Anglo-Saxon treasures found at Sutton Hoo. Bilbo’s gift of a pair of silver spoons to Lobelia Sackville-Baggins is reminiscent of the two silver baptismal spoons found in the royal Anglo-Saxon grave:

Family matters: The importance of genealogies

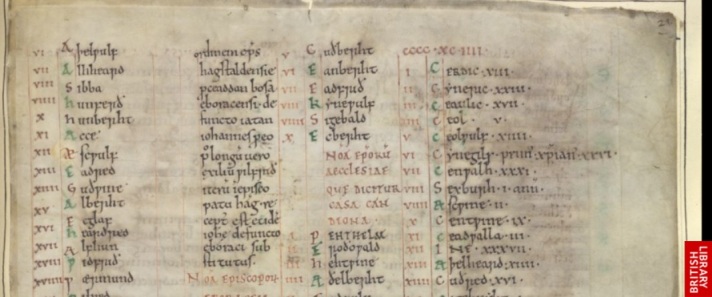

Another habit shared by Anglo-Saxon and Hobbit alike is an interest in filling books with genealogical information. In his prologue to The Fellowship of the Ring, Tolkien explains that Hobbits were keen to draw up long and elaborate family-trees and loved to set out such trees and lists in books. The Anglo-Saxons were little different in this respect: the famous Anglo-Saxon Chronicle contains up to eighteen genealogies of various royal houses, scattered throughout its annalistic narrative. Such royal genealogies also appeared in collections without any intervening text. A case in point is the so-called Anglian Collection, a collection of Anglo-Saxon regnal lists and genealogies (this Wikipedia page is highly informative):

These endless lists of names do not make for exciting reading. Tolkien remarked the same of the genealogical information contained at the end of the Red Book of Westmarch: “all but Hobbits would find them exceedingly dull”; Hobbits…and Anglo-Saxons, it would seem!

If you liked this post, you may also be interested in:

What a fun post! I had no idea that there were so many similarities between Hobbit and Anglo-Saxon society.

LikeLike