For a bonus question on one of my Old English literature exams, my students used their artistic talents to draw scenes from The Battle of Maldon. Together, these doodles cover almost the entire poem and document how well (or how badly) my students remembered the poem.

Drawings have long since been used for the purpose of teaching (for an example from the Anglo-Saxon period see Teaching the Passion to the Anglo-Saxons: An early medieval comic strip in the St Augustine Gospels). On occasion, I use my own drawings to spice up my lectures (such as my Anglo-Saxon Anecdotes) or explain complicated bits of Anglo-Saxon literature (e.g., The Freoðuwebbe and the Freswael: A Comic Strip Reconstruction of the Finnsburg Fragment and Episode). For last year’s third-year Old English literature exam, I decided to turn the tables on my students. I had them each draw a scene from the Old English poem The Battle of Maldon for a bonus point (worth 1% of the final grade) and the results were both hilarious and insightful. While the exercise was intended as a bit of a gag, their doodles actually allowed me to see which events from the poem had captured their interest; how they (mis)remembered certain passages; how few of them could spell the name of the English leader Byrhtnoth correctly; and which scenes, apparently, made no impact on them at all (e.g., no one pictured the loyal retainers fighting on to die alongside their lord!). Here follows a selection of my students’ drawings, along with some commentary.

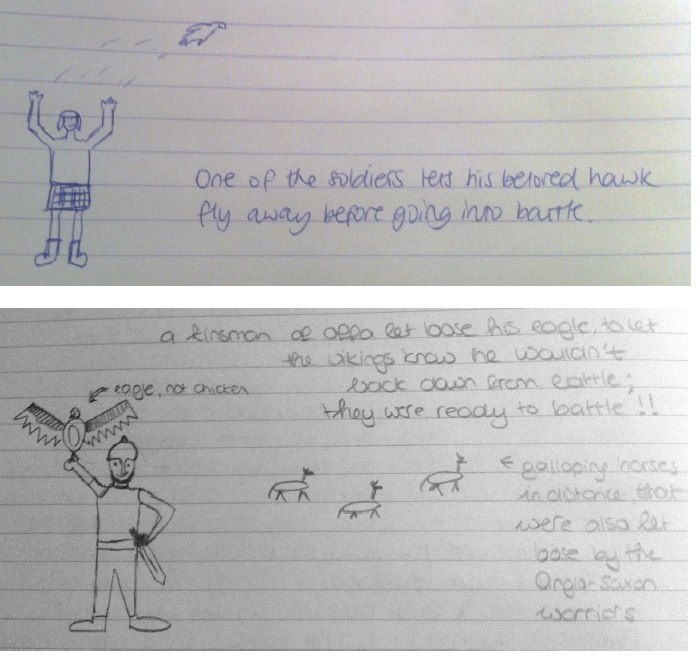

i) Release the hawk!

In the opening lines of the extant version of The Battle of Maldon, the kinsman of Offa releases his “leofne…hafoc” [beloved hawk] (ll. 4-5); a scene, which apparently, struck a chord with these two students. As the second student points out, Offa’s release of the hawk, as well as the decision of the English to drive away their horses, was intended to strengthen the morale of the English troops – they had burned their bridges (or: released their beloved hawks) and there would be no turning back!

ii) ‘Give us dollah!’

The next two students have drawn how the Vikings demand tribute or, as the second drawing suggests, “dollah”, which (apparently) is slang for money or danegeld [the term used for the tribute paid by the Anglo-Saxons to the Dane – bonus point!]. The English respond reluctant: “not a chance!” according to the first student; the second student is closer to the mark: “kill them with spears!”, “poisoned spears!”, some of the English shout – reflecting the English leader Byrhtnoth’s original response to offer the vikings “garas …ættrynne ord and ealde swurd” [spears, poisoned spears and old swords] (ll. 46-47) .The second drawing also shows what happens next: the Vikings ask to be allowed to pass and “Byrthroth” lets them – an important scene that inspired many other students as well…

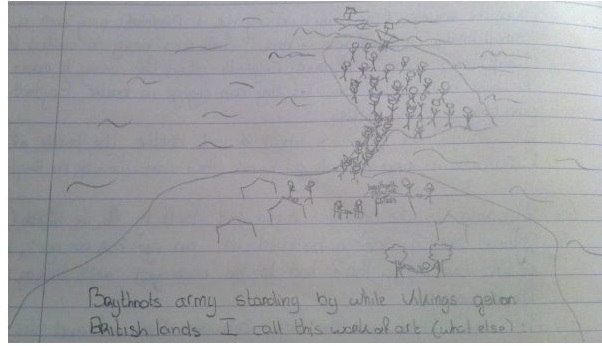

iii) Let them pass!

This student has drawn the strategic advantage of the English army, led by “Byrhnoth”: the Vikings had to cross a narrow tidal causeway to get to the other side. (Ooo! Horned helmet alert!)

This student has the Vikings threaten to “hurt you and your mum”; stick figure “Byrhnoth” is unimpressed and says “You may cross over so we can fight like real men. I want glory!”.

This student depicts “Brythnots army standing by while Vikings get on British lands”. With a keen eye for detail, the student has the English play games of football, chess and whiff-whaff (and one English warrior even sleeps in a hammock!), while the Vikings cross to the main land.

Another bridge-crossing scene – one English warrior shouts “Yay! Fair battle!” and another shouts “Swilce ofermod!”. The latter, of course, refers to the original poet’s remark that the English leader Byrhtnoth acted out “his ofermode” (l. 89) [his excessive pride].

iv) The beasts of battle await…

This student has remembered one of the recurring typescenes of Old English heroic poetry: the beasts of battle that show up at the end of a battle to devour the dead bodies. They also make an appearance in The Battle of Maldon: hremmas wundon / earn æses georn” [ravens wound about, eager eagles of carrion] (ll. 106-107).

This student has remembered one of the recurring typescenes of Old English heroic poetry: the beasts of battle that show up at the end of a battle to devour the dead bodies. They also make an appearance in The Battle of Maldon: hremmas wundon / earn æses georn” [ravens wound about, eager eagles of carrion] (ll. 106-107).

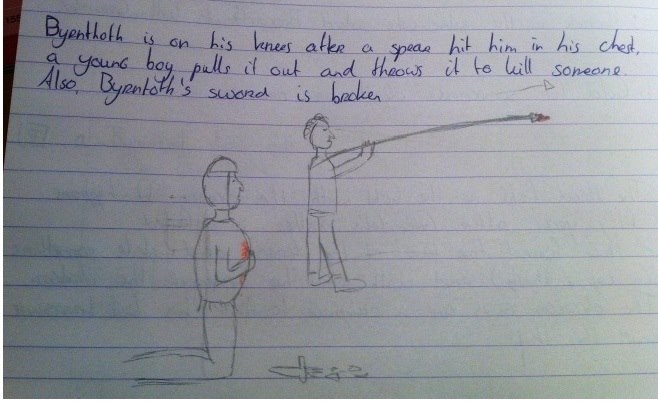

v) The death of Byrhtnoth

I always tell my students that this scene is pure Hollywood: the old leader “Byrnthoth” – a “har hilderinc” [grey-haired warrior] (l. 168) – goes down, the young warrior Wulfmær – “hyse unweaxen” [a young man, not fully grown] (l. 152) – takes revenge! I am glad that at least one of them took note. Not sure where the broken sword comes from though…

Another student also remembered the scene (and the correct spelling of the leader’s name!), and then went all Harold Godwinson on the offending Viking spear-thrower!

vi) How not to be a hero

Of course, not all English warriors were as courageous as young Wulfmaer. This student remembers how the sons of Odda fleed the scene, taking with them the horse of their stricken leader “Byrtnoth”. In the poem, all three sons of Odda flee the scene and, in the mind of the next student, they all did so on the same horse:

I find it intriguing to see how none of the students seem to have been inspired to draw the near-suicidal loyalty of the English warriors after their lord has been cut down. Even the poem’s most famous lines “Hige sceal þe heardra, heorte þe cenre / mod sceal þe mare, þe ure mægen lytlað” [Mind must be tougher, heart must be bolder, courage must be greater, as our strength becomes less] did not get a mention – odd, given that it is the perfect mindset for an exam!

vii) Wow, very ofermod, much Anglo-Saxon, wow

Wow, indeed.

Wonderful post! Wow, indeed!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Grendel's (M)Others.

LikeLike

This is brilliant. Made me smile and chuckle.

LikeLike

Wat leuk – link geplaatst op de Facebookpagina van de FGW!

LikeLike