Henry Sweet (1845-1912) was a remarkable scholar who laid some of the foundations for the academic study of Old English. This blog provides an overview of Sweet’s publications with respect to Old English and Anglo-Saxon texts. It also relates how a nineteenth-century Dutch student of Old English felt utterly insulted by Sweet, who had ignored him despite his pointing out several mistakes in Sweet’s published work.

Henry Sweet (1845-1912): A formidable scholar with an abrasive personality

Henry Sweet is known as one of the founding fathers of the scholarly study of Old English: a reputation he owes to his highly popular textbooks of Old English: The Anglo-Saxon Reader and The Anglo-Saxon Primer. Even today, many students of Old English will own one or more of Sweet’s works (his Primer and Reader remained classroom texts for at least a century after their publication and can be bought for a penny in most second-hand book stores). Sweet himself probably got his first grounding in Old English from T. O. Cockayne (1809-1873), a teacher at King’s College School, London, which Sweet attended from 1861 to 1863. Sweet later studied comparative and Germanic philology at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, and read classics in Baliol College Oxford, where he got a fourth-class BA degree in 1873. This rather mediocre degree was likely due to his energetic study of the Germanic languages, which he favoured over the study of Latin and Greek. Indeed, by the time he graduated, he had already published an edition of the Old English translation of Gregory’s Pastoral Care (1871-1872) and had begun work on a dictionary of Old English (which would eventually be published in 1896). Sweet had also read several papers to the Philological Society, which he would serve as its president from 1876-1878. Thus, while Sweet failed to impress as a classicist, he became a remarkable specialist in the field of comparative linguistics, phonetics and the study of Old English (MacMahon 2004).

Henry Sweet was more respected abroad than he was in England. Despite his impressive list of publications, he had to wait until 1901, when, aged fifty-five, he was offered a position at a university: the readership of phonetics at the University of Oxford. By contrast, as MacMahon (2004) outlines, institutions outside of Britain were more appreciative of Sweet: he was awarded an honorary PhD degree in 1875 by the University of Heidelberg and he was made a member of various academic societies abroad, including the Munich Academy of Sciences, the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences, the Royal Danish Academy and the International Phonetic Association (which he served as its president from 1887 to his death). He had also been offered various university chairs on the Continent, where the study of Old English and comparative philology was much more advanced than in Britain. Sweet had declined those offers, because he felt he had a mission back home.

Sweet’s mission was the promotion and establishment of the scientific study of linguistics, particularly Old English, in England. In this field of inquiry, continental scholars outshone the English; a fact Sweet himself often lamented. He voiced his concerns in the prefaces to his publications and in personal correspondence. An example of the latter is the following excerpt of a letter by Sweet to P. J. Cosijn (1841-1899), Professor of Germanic Philology at the University of Leiden, The Netherlands:

Sweet’s crusade to turn the academic tide was partially fuelled by his patriotism. As Frantzen (1990) has observed, Sweet “saw language study as a matter of national pride” (p 72). Sweet’s endeavours resulted in various didactic works, suitable for a whole range of students of Old English – from dummies to experts, Sweet’s works catered to all (see below).

With the quality of his scholarship beyond any doubt, one of the reasons why Sweet never managed to land a university teaching job may have been his abrasive character. As Niles (2015) puts it, “Sweet was a man with a sharp tongue who was not known for living up to the promise of his name” (p. 249). MacMahon (2004) also notes how “Sweet’s personality was partly to blame for his lack of success in Britain”. Interestingly, some of his nasty traits were immortalised by the playwright George Bernard Shaw who based the character Professor Higgins in Pygmalion (1912; better known, perhaps, as its musical adaptation My fair lady) on Henry Sweet. At the end of this blog post, we will see that Sweet also wasn’t very kind to a Dutch student who desperately wanted to get acquainted with the “gentleman from Baliol College Oxford”.

Publications relating to Old English

Thanks to the Internet Archive, most of Sweet’s publications with regard to Anglo-Saxon texts and the Old English language are now freely available. Below follows a chronological overview of his works (I have limited my selection to works touching on Old English; Sweet also published works on Middle English, Icelandic and general linguistics):

- King Alfred’s West-Saxon Version of Gregory’s Pastoral Care: With an English Translation, the Latin Text, Notes, and an Introduction (1871-1872): An edition and translation of the Old English translation of the Gregory the Great’s Cura Pastoralis. Still the standard edition of this text.

- An Anglo-Saxon Reader in Prose and Verse: With Grammatical Introduction, Notes, and Glossary (1876). A second, revised and enlarged edition (1879); a third, revised and enlarged edition (1881); a fourth, revised and enlarged edition (1884). The text of the fourth edition was retained without further alterations through to the sixth edition (1888). The seventh edition (1894) was partially re-written and enlarged.

- An Anglo-Saxon Primer, with Grammar, Notes, and Glossary (1882). A second edition, with minor corrections, was published in the same year. A third edition with many improvements appeared in 1886. The text remained the same for the fourth edition (1887), through to the sixth edition (1890), seventh edition (1893) and eighth edition (1905). In 1953, Norman Davis revised the ninth edition of Sweet’s Primer.

- The Épinal Glossary, Latin and Old-English (1883). An edition of the late seventh-century glossary, along with a photo-lithograph facsimile of the manuscript. Unfortunately, this edition has not been digitized by the Internet Archive. Those interested in the Épinal glossary are in luck, since the manuscript itself has been made available and can be accessed here, along with a transcription.

- King Alfred’s Orosius. Part 1: Old-English Text and Latin Original (1883): An edition of the Old English translation of Orosius’s Historiae adversus paganos, along with the Latin source text. No modern English translation or glossary is provided.

- Extracts from Alfred’s Orosius (1885): Extracts from the 1883 edition of the same work, with limited glossary. Published as a supplement to his Anglo-Saxon Reader. A second edition appeared in 1893.

- Selected Homilies of Ælfric (1885). Extracts from Benjamin Thorpe’s edition of Ælfric’s Catholic Homilies, with limited glossary. Published as a supplement to his Anglo-Saxon Reader. A second edition, with some additions to the glossary, appeared in 1922.

- The Oldest English Texts (1885). According to the preface, this edition was “intended to include all the extant Old-English texts up to about 900 that are preserved in contemporary mss., with the exception of the Chronicle and the works of Alfred”. Edition includes glossaries, genealogies, charters and glosses. No translation is provided, but there is a full glossary.

- A Second Anglo-Saxon Reader: Archaic and Dialectal (1887). Another supplement to Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Reader, featuring a selection of non-West Saxon texts and older material (e.g. glossaries and charters). In part, this is an abridged version of his Oldest English Texts.

- The Student’s Dictionary of Anglo-Saxon (1896). An abridgement of the Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (which has now been digitized here: http://www.bosworthtoller.com/ ) .

- First Steps in Anglo-Saxon (1897): A short, simplified beginner’s guide to Old English with texts and glossary. Texts include Ælfric’s Colloquy and a prose paraphrase of Beowulf in Old English, by Sweet himself.

- Collected Papers of Henry Sweet (1913). A posthumous collection of Sweet’s shorter writings, arranged by Henry C. Wyld. The collection includes various notes on Old English sounds and etymologies. An interesting piece is Sweet’s earliest paper: ‘The History of TH in English’ (1869), with an amusing afterword by Sweet’s former teacher T. O. Cockayne (1809-1873), which is interspersed with þ’s and ð’s – the Old English symbols for TH.

A glance at Sweet’s publications reveals that a good portion of his publications were intended for students of Old English. A remarkable feat, given that Sweet never really held a teaching job. Indeed, the fact that he had no students to teach actually made it hard for Sweet to improve his didactic works, as he himself lamented in the preface to third edition of the Anglo-Saxon Primer:

If I had any opportunity of teaching the language, I should no doubt have been able to introduce many other improvements; as it is I have had to rely mainly on the suggestions and corrections kindly sent to me by various teachers and students who have used this book, among whom my special thanks are due to the Rev. W. F. Moulton, of Cambridge, and Mr. C. Stoffel, of Amsterdam.

Here, Sweet sounds appreciative of the corrections he had received. Not every reader’s suggestion was greeted with such grace, however, as the case of Dutch schoolmaster and autodidact student of Old English G.J.P.J. Bolland (1852-1922) reveals…

“A schoolmaster need not expect deference from a gentleman of Baliol College Oxford”: How Henry Sweet ignored and insulted a helpful, nineteenth-century Dutch student

At the end of the nineteenth century, the Dutch schoolmaster G. J. P. J. Bolland (1852-1922) had decided to devote himself to the study of Germanic languages, focusing on Old English in particular. Thanks to a grant of sorts, Bolland had been able to spend a few months in London, where he trained himself in the academic study of Old English. Naturally, he had read some of Sweet’s publications and even had some suggestions for improvement. As it turns out, Sweet did not want to meet with Bolland, who, being utterly insulted, turned to his mentor, Professor of Germanic Philology in Leiden, P. J. Cosijn. Bolland wrote to Cosijn on October 10, 1879:

..our [Dutch] linguists seem less condescending than the English half-thinkers appear to me. It is with emphasis and without flattery, that I wouldn’t dare to compare you as a Germanicist to H. Sweet; even if that gentleman were the editor of the Pastoral Care [the Old English translation of Gregory’s Cura Pastoralis] a thousand times over! And still, you refer me to his work on phonetics as being authoritative?

Bolland then lists a number of errors he had found in Henry Sweet’s A History of English Sounds from the Earliest Period (1874), a ground-breaking work in historical English phonology. Bolland’s errors include Sweet’s suggestion that Modern English mate came from Old English gemaca ‘companion’ (while Sweet’s suggestion makes sense semantically, the change from /t/ to /k/ is unlikely; indeed, the OED notes that English mate is a borrowing from Middle Low German mát, while gemaca still survives today in Scottish and regional English usage as make ‘partner, spouse’. In other words, Bolland was right: mate and gemaca are not related). Another one of Bolland’s faults with Sweet was the latter’s assumption that the Anglo-Saxon name Offa was a Germanicized form of the name Aba (there is no evidence for this, whatsoever). Bolland’s other remarks concern the phonological status of the sound eaa in Old English (which Bolland considered doubtful) and Sweet’s apparent ignorance that Old English dǽl ‘part’ was an i-stem (which Bolland thought was deplorable). A harsh review, indeed!

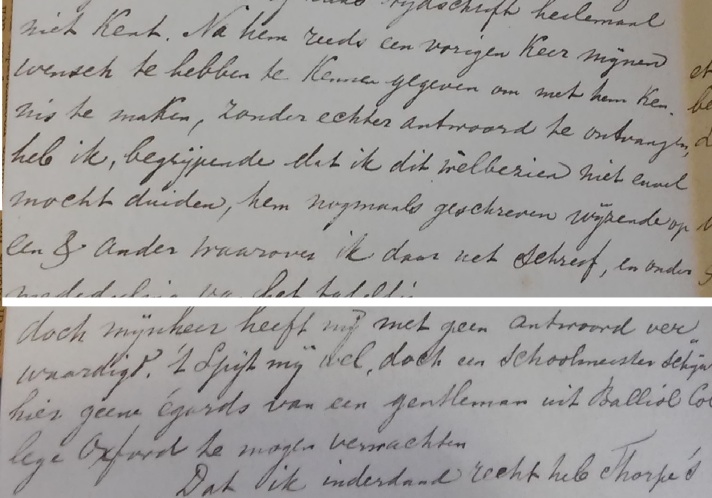

Bolland explains to Cosijn that he had asked for a meeting with Sweet, but that the latter had never returned his calls:

Having expressed my desire to get acquainted with him some time before, but having received no answer, I have, thinking no evil of this, written to him again, pointing to one thing and another which I have written about above…but that Sir did not deign to give me an answer. I am awfully sorry, but it seems a schoolmaster [Bolland had worked as a school master in Katwijk, The Netherlands, the year before] need not expect deference from a gentleman of Baliol College Oxford.

His grievance concerning the fact that Sweet had not taken the time to meet with him appears to have lingered with Bolland. This much becomes clear from a letter written by Cosijn to Bolland, a year later (24 August, 1880). It seems Bolland had managed to get acquainted with Richard Morris (1833-1894), another English philologist; the two had compared notes on Sweet’s behaviour and Bolland had shared this again with Cosijn. Cosijn wrote:

Morris’s judgement concerning Sweet appears to me to be sound. I have not heard from Sweet for a long time, even though I urged for a speedy reply. But Sweet appears to be ‘this’ today and ‘that’ again, tomorrow.

In the end, Henry Sweet never met with G. J. P. J. Bolland, much to the latter’s chagrin. Perhaps Bolland eventually found some solace in the fact that Sweet’s revised second edition of A History of English Sounds, published in 1888, no longer featured any of the errors pointed out by Bolland:

Perhaps, Sweet had read Bolland’s letter after all?

This is the second in a series of blogs related to my research project “My former Germanicist me”: G. J. P. J. Bolland (1854-1922) as an Amateur Old Germanicist , which explores how a Dutch student at the end of the nineteenth century tried to master Old English. The first one can be found here: Benjamin Thorpe: The Man Who Translated Almost All Old English Texts

Texts referred to:

- Frantzen, Allen J. The Desire for Origins. New Language, Old English, and Teaching the Tradition, New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press, 1990.

- Niles, John D. The Idea of Anglo-Saxon England 1066-1901: Remembering, Forgetting, Deciphering, and Renewing the Past, Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015.

- MacMahon, M. K. C. ‘Sweet, Henry (1845–1912)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2006 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/36385, accessed 29 May 2016]

Reblogged this on pmayhew53.

LikeLike